The First World Empire: Portugal/ War and Military Revolution | Heler Carvalhal, André Murteira e Roger Lee de Jesus

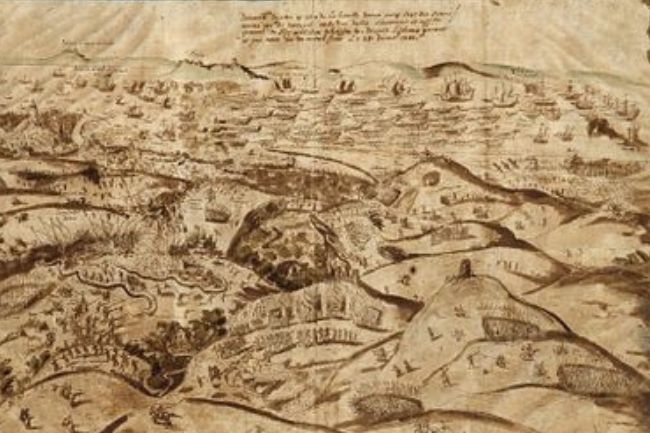

Croquis do sítio e ordem de batalha de Alcântara diante de Lisboa, por mar e terra. Detalhe de capa de “The First World Empire: Portugal, War and Military Revolution” | Imagem: Wikipedia

2Yet, as the authors of this edited volume rightly note, in the debate on the military revolution, Portugal has in fact been oddly overlooked. As Miguel Geraldes Rodrigues notes in chapter 10 “the historiography of the Portuguese Empire has, puzzlingly, greatly overlooked and ignored most of its discussions, especially given Portugal’s pioneering role in the European oceanic expansion” (p. 171). This edited volume seeks to address this lacuna in the scholarship and its thirteen chapters cover a lot of ground. To structure a field of inquiry that of necessity will range widely in both its geographical and chronological scope, the book has been divided into four parts, preceded by a preface and a foreword which both present some of the rationale of the book, with the latter also laying out the structure of the work. The first part “Fortifications and military revolution” is focused on fortification design and engineer education. Its three chapters deal with the designs of Azzemour in the sixteenth century, the training of Portuguese engineers and the role of engineers in the defense of Portugal in the war of 1640-1668. Part two deals with another aspect of the military revolution debate: its impact on the size of armies and the rise of the fiscal state. Its chapters in turn deal with army size and expenditure in the sixteenth century, with the question whether we can discern a military revolution in mainland Portugal, and with the war for colonial Brazil against the Dutch in the seventeenth century.

3The third section, entitled “Tradition and innovation in warfare” again is composed of three chapters, dealing with the impact of the Iberian Union on the composition of artillery in Portugal and the origins of its master cannon founders. In the field of acquiring artillery and gunfounders, the Iberian Union actually made it easier for Portugal to acquire the services of expert gunners, and the centralization of gunners and artillery resources under the captain-general of artillery actually defied the separation of crowns as agreed by Phillip II in the Cortes of Tomar in 1581. Chapter eight of the book details the Portuguese military expeditions to Southeast Asia sent between 1597 and 1606 in an attempt to stymie the rise of Dutch power in the region. André Murteira convincingly argues that the defeat of the various Portuguese fleets cannot be simply explained by Dutch technological superiority: the Asian polities allied with the Dutch were also able to inflict defeats on the Portuguese. This was thus not simply a matter of the Dutch being “up to date” with European practice and the Portuguese lagging behind.

4The final chapter of this section reassesses Portuguese military superiority in land warfare in Asia in the sixteenth century. Any military advantage that the Estado da Índia might have enjoyed in western India in this period certainly did not allow it to engage in large-scale expansion and control of territory. Roger Lee de Jesus argues that Jeremy Black, rather than Geoffrey Parker, is a better guide to Portuguese-Indian military interactions in this period and this arena. Finally, the four chapters of part four, which is titled “Cultural exchange and circulation of military knowledge” focus on the effect of the military revolution overseas. The chapters cover the Portuguese conquest of Angola, the role of the Portuguese as suppliers, brokers and allies in Makassar in the seventeenth century, the development of artillery in China and the role of Portuguese cannon. Finally, Tonio Andrade discusses the concept of military revolution in the context of East Asia and proposes that we should see it as a global, rather than purely European, phenomenon.

5Collectively, the chapters of The First World Empire also clearly show the double face of the military revolution debate. There has always been a debate about whether “revolution” was the proper term to use and different ideas arose about the chronology and the drivers behind the process. But increasingly, historians seem to talk about two entirely different processes. On the one hand, there is the role that changes in warfare played in state-formation processes in Europe itself. This line of argumentation holds that changes in warfare required increases in army size and expenditure on everything from bastion-trace fortifications, ships and cannon. The fiscal pressures in turn made changes in the relation between the state and its subjects necessary. Increased taxation, creation of public debt and an increasing disarmament and subordination of local elites to the central state followed. This line of reasoning is examined in this book by Fernando Dores Costa and Hélder Carvalhal. In their two respective chapters, they argue that this process did not play out as described above in Portugal. Tonio Andrade, in the book’s final chapter, provides an interesting assessment in which he turns the relation between state formation and gunpowder weapons on its head. Rather than changes in military technology begetting changes in state formation, centralized states capable of maintaining standing armies were a precondition for implementing tactical changes such as volley fire which gunpowder weapons truly made effective in the field.

6On the other hand, there is the military revolution debate as it pertains to the relations of European states with non-Europeans from the late fifteenth century onwards. This aspect of the military revolution debate is less concerned with the fiscal pressures of changing warfare but more focused on actual combat itself. European weaponry, ships, fortifications, and tactics have all been argued to have given Europeans advantages when confronted with non-European foes. Miguel Geraldes Rodrigues examines this aspect in relation to the Portuguese conquest of Angola in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, arguing that the Portuguese experience of warfare in Angola does not back up a claim to technical or tactical superiority being decisive.

7Perhaps, though, it would be prudent to disentangle the two aspects of the military revolution debate described above – state formation in Europe and overseas military superiority. For it seems eminently possible to argue against the existence of the military revolution in Portugal based on the absence of changes in state-formation, while maintaining that European siege and naval warfare gave the Portuguese an advantage in Asia at the same time. This is a valuable contribution which the Portuguese case especially brings to light. This could have been more strongly formulated by the editors by a concluding chapter which would draw on the rich cases elaborated in the separate chapters. Such a chapter would have afforded them a platform to propose a research agenda for the future. What do we now know, and what do we still need to know? Which particular cases, such as sieges and battles, or processes do we yet need more information on? How could the Portuguese case specifically help us to fill these voids? The book is a valuable resource for students working on the Portuguese empire and the military revolution as a global phenomenon. Giving some suggestions for future fruitful avenues of inquiry would make it doubly valuable.

8No single volume can of course cover all aspects of Portuguese military history in Europe and overseas, but this book makes a valuable contribution to the field. Especially for a non-Lusophone audience, this is a very good first start to examine the military revolution debate in relation to the Portuguese case. The chapters are perhaps best considered separately. There is a bit of an overlap since every chapter lays out the methodological and historiographical groundwork anew. The separate bibliographies with the chapters make them good introductions into the literature for their specialist subjects. This makes the book especially well-suited to use in classes on the military revolution debate, as well as for scholars working on the field seeking to broaden their horizon.

Notas

1 The idea was first proposed by Michael Roberts in The Military Revolution, 1560-1660: An Inaugural Lecture Delivered Before the Queen’s University of Belfast (Belfast: M. Boyd, 1956) and was later taken up by Geoffrey Parker who changed the chronology and focused on the importance of bastion-trace fortifications: Geoffrey Parker, The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500-1800 (Cambridge: CUP, 1988).

2 See, inter alia, Jeremy Black, A Military Revolution? Military Change and European Society 1550-1800 (MacMillan Press: Basingstoke, 1991); Clifford J. Rogers (ed), The Military Revolution Debate: Readings on the Military Transformation of Early Modern Europe (Taylor and Francis: London, 1995).

3 See for instance: Tonio Andrade, Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China’s First Great Victory over the West (Princeton: PUP, 2011); idem, The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History (Princeton: PUP, 2017); Kaushik Roy, Military Transition in Early Modern Asia, 1400-1750: Cavalry, Guns, Government and Ships (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2014); J.C. Sharman, Empires of the Weak: The Real Story of European Expansion and the Creation of the New World Order (Princeton: PUP, 2019).

Resenhista

Erik Odegard – International Institute for Social History, The Netherlands. E-mail: erik.odegard@iisg.nl

Referências desta resenha

CARVALHAL, Helder; MURTEIRA, André; JESUS, Roger Lee de. The First World Empire: Portugal, War and Military Revolution. London and New York: Routledge, 2021. 302p. Resenha de: ODEGARD, Erik. Ler História [Online], 80 | 2022. Acessar publicação original.