Posts com a Tag ‘Séc. 19’

A educação do corpo nas escolas do Rio de Janeiro do século XIX | Victor Andrade de Melo

Para Soares (2014) a educação do corpo se caracteriza pela progressiva repressão das manifestações corporais. Assim, educar o corpo, de acordo com autora, é torná-lo adequado ao convívio social, bem como inseri-lo processualmente em mecanismos de aprendizagens que buscam encobrir e apagar comportamentos selvagens, trazendo à tona características pacíficas. Nesse sentido, a educação do corpo pode se manifestar em diferentes espaços e contextos, desde instituições formais como a igreja e a escola, até em clubes sociais e esportivos, parques de diversões, entre outros âmbitos comuns da vida pública. A educação do corpo, portanto, se trata de uma potente e ampla rede de discursos e significados que permeiam um conjunto variado de normas, proibições e consentimentos diretamente vinculados aos corpos e as dimensões culturais, econômicas, políticas e sociais de cada tempo e localidade – características essas que vêm permitindo aos pesquisadores escreverem uma história da educação fundamentando-se no respectivo conceito nas mais variadas esferas e lugares.

Nessa esteira, o livro resenhado se trata de uma contribuição para a história da educação, especialmente para as discussões ligadas às iniciativas de educação do corpo relacionadas com as práticas corporais e o espaço escolar. A obra intitulada “A educação do corpo nas escolas do Rio de Janeiro do século XIX”, publicada pela editora 7letras, foi escrita pelo pesquisador Victor Andrade de Melo, professor da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. O livro é organizado em quatro capítulos, e tem como objetivo discutir como foram mobilizadas as pioneiras experiências de ensino de práticas corporais nos colégios da capital fluminense, sobretudo nos tempos do império (1822-1889). Devemos destacar que o recorte temporal abordado pela autoria foi um período emblemático na história do Rio de Janeiro e do Brasil. Representa uma época singular no que tange a sua formação enquanto Estado-nação em um território que passou de colônia para império. Foi um momento de intensas mudanças no que diz respeito ao desenvolvimento e adesão a ideias de modernidade e progresso, elementos esses que o autor é zeloso em considerar ao longo da obra. Leia Mais

Libro de acuerdo para pleitos de recusaciones de oidores y para pleitos propios de oidores y de su família/año 1564 | Ana María Presta

En la publicación de este libro se conectan el quehacer de la historiadora Ana María Presta (a quien se debe obras fundamentales para la comprensión de las dinámicas sociohistóricas en Charcas en la segunda mitad del siglo XVI), las investigaciones iushistoriográficas emprendidas por el historiador Sergio Angeli en el estudio de los oidores de la Audiencia, el estudio sistemático de la obra jurídica de Juan de Matienzo desarrollada por el historiador Germán Morong; además de la historia de los proyectos editoriales impulsados por el Archivo y Biblioteca Nacionales de Bolivia. En 2007, se publicaron los Acuerdos de la Real Audiencia de La Plata de los Charcas, en 10 volúmenes, bajo la dirección de José Miguel López Villalba. De acuerdo con Marcela Inch (1946-2015), exdirectora del ABNB, el proyecto editorial comenzó a gestarse a fines de la década de 1990 por iniciativa de la Corte Suprema de Justicia. A inicios del siglo XXI, Josep Barnadas (1941-2014) formuló un anteproyecto por petición del ABNB. Finalmente, en 2004, el ABNB presentó el proyecto de transcripción y publicación de los Acuerdos al Programa de Justicia de AECI. Este fue aprobado en noviembre de 2005 y ejecutado durante trece meses.

En el volumen 9 se publicó un conjunto de documentos indispensables para el estudio de la actividad judicial en la Audiencia de La Plata: “Penas de Cámara, 1566-1813”, “Testimonios de Autos Acordados, 1664-1826” y “Pleitos propios, 1564”. Este último es objeto de una nueva transcripción en el libro editado por Ana María Presta. ¿Qué ha justificado volver sobre un documento ya publicado? Para Ana María Presta, junto con los errores de transcripción y la omisión de las notas en latín redactadas por el licenciado Juan de Matienzo, la edición descuidó no solo que se trataba de un documento escrito por los oidores de la Audiencia de La Plata, sino que también el “valor iustoriográfico de la pieza y el contenido político que guardan sus páginas, más allá de soslayar la cultura jurídica del oidor vallisoletano que no es otra que la de su época” (p. 7). En esta perspectiva, la edición de Ana María Presta ofrece una copia facsimilar acompañada de una transcripción crítica y anotada del Libro de acuerdo para pleitos de recusaciones de oidores. A este califica de rara avis por cuanto se trata de una documentación que no se encuentra con frecuencia en las audiencias americanas. De hecho, es el único que se halla entre los papeles de la Audiencia de Charcas, aunque no fue infrecuente el recurso a la recusación. Leia Mais

«Les péruviens auparavant nommés indiens ». Discours sur les populations autochtones des Andes dans le Pérou indépendant (1821-1879) | Maud Yvinec

Las Prensas Universitarias de Rennes nos ofrecen, con este volumen, un detallado estudio textual sobre la representación del indio en el Perú, desde la declaración de independencia en 1821 hasta la guerra con Chile, dos momentos que interrogan los fundamentos ideológicos y políticos del país. Al prefacio de Bernard Lavallé (p. 9-11) le siguen una introducción general (p. 13-25) y cuatro partes temáticas que reúnen tres capítulos cada una. La conclusión general (p. 298-293) cierra el contenido de la obra, mientras que dos anexos (el mapa del Perú de Mariano Felipe Paz Soldán en 1865 y una lista de eventos cronológicos) completan el trabajo. El libro pone a dialogar escritos políticos de circunstancia, producción científica, discursos parlamentarios y piezas literarias diversas. La variedad de fuentes constituye, en este sentido, un primer punto notable de esta obra. Una centena de periódicos permiten cubrir, globalmente, un periodo en el que la irregularidad de la prensa es, salvo raras excepciones, la regla. A lo que se suma un volumen considerable de impresos de la época. El resultado es un análisis textual, a la vez general y detallado, de las concepciones que representan a la población autóctona, comenzando desde los padres fundadores y pasando por la juventud romántica, la naciente arqueología nacional, los debates sobre el tributo indígena y las preocupaciones sobre el analfabetismo. La obra ofrece una síntesis ambiciosa y muy bien lograda.

La introducción general señala la perspectiva y las definiciones que estructuran el conjunto del libro. Analizando la circulación y la evolución de estereotipos y lugares comunes, la obra logra exitosamente une historia cultural de las representaciones. Basta dar un vistazo a la historia intelectual del Perú para ver hasta qué punto la cuestión indígena estructura el debate ideológico desde sus inicios republicanos. Leia Mais

Saber hacer y decir en justicia. Culturas jurídicojudiciales en la zona centro-sur de Chile (1824-1875) | Víctor Brangier

En Saber hacer y decir en justicia. Culturas jurídico-judiciales en la zona centro-sur de Chile (1824-1875), Víctor Brangier ofrece el trabajo realizado en su tesis doctoral. En el contexto de la historia de la justicia, su estudio aborda el uso estratégico de argumentos y prácticas que actores legales pusieron en práctica en casos penales judicializados para persuadir a los jueces con el fin de obtener algún beneficio durante el siglo XIX en Chile. El argumento principal de la obra es que los justiciables tenían un conocimiento sobre el mundo judicial que les permitía navegar sus casos legales de una forma estratégica con miras a maximizar las posibilidades de un resultado favorable debido a que compartían con los jueces -en particular jueces legos sin formación jurídica- un mismo mundo sociocultural, lo que hacía que tuviesen valores similares, por lo cual los jueces eran propensos a empatizar con sus argumentos. Leia Mais

En busca de una opinión pública moderna. La producción hemerográfica de los españoles exiliados en Inglaterra y su apropiación por la prensa mexicana/1824-1827 | María Eugenia Claps Arenas

Este libro corresponde a la publicación de una tesis de maestría presentada en la UNAM en 1999, que, como muchas otras y a veces de manera indebida, dormía en una biblioteca universitaria. De hecho, estos ejercicios académicos constituyen un corpus desigual que, por su naturaleza misma y sus limitantes de extensión, ofrecen a menudo una historia sumamente fragmentada. Esta última consideración se verifica par ticu lar men te cuando se trata de la historia de la prensa mexicana, cuyo peculiar desarrollo, iniciado en la última década del siglo XX, desbroza desde entonces un territorio gigantesco. Publicar una antigua tesis no es empresa sencilla. Requiere a la vez selección e integración pertinentes de la abundante historiografía considerablemente aumentada en los últimos 20 años, y, en consecuencia, y más allá del rastreo de la información o del dato bruto esparcido en la bibliografía, una revisión a veces profunda de las consideraciones analíticas iniciales, elaboradas en una época remota. Agregamos que la historia de la prensa oscila de manera permanente entre el uso de la prensa como fuente para la historia y el estudio de la prensa como objeto de estudio en sí, es decir, como medio de comunicación. Este último enfoque es el menos común, en particular para el estudio de la temprana prensa decimonónica. Supone la ampliación del campo de observación, la ubicación y contextualización de la esfera pública impresa urbana (que no refleja a toda “la sociedad”), en este preciso periodo, no realmente subyugada por los periódicos sino más bien sumergida en la abundante y dominante “folletería”, así como cierta distancia objetiva respecto a los conte nidos o más bien discursos periodísticos, entonces contemplados en tanto que elementos de complejas y cambiantes estrategias mediáticas. Asimismo, supone debatir y aclarar conceptos y categorías históricas problemáticas como son, por ejemplo y en el presente caso, “opinión pública”, “apropiación” o la llamada “modernidad”. Leia Mais

El Senado mexicano y las reformas a la Constitución a finales del siglo XIX | Ángel Israel Limón Enríquez

En 2016 un nutrido grupo de latinoamericanistas nos reunimos en LASA para conocer cómo estábamos en materia de congresos en América Latina. El panorama no fue halagüeño. Lo que había predominado en las grandes historias del continente americano -por ejemplo, Leslie Bethell y John Lynch- eran estudios sobre caudillos, golpes militares, cacicazgos, corporaciones económicas y eclesiásticas, personajes artísticos y culturales, redes familiares y empresariales. Pero casi nada sobre las asambleas o congresos como actores centrales de los diseños del cambio político en el siglo XIX (lo mismo se puede decir sobre los estudios del poder judicial). Esto tiende a cambiar gradualmente -recomiendo el dossier de la revista alemana Jarhbuch, 2019-, aunque todavía no alcanza a ser suficiente para el tamaño de lo que debemos cubrir en lo espacial y temporal del ámbito latinoamericano. Leia Mais

A Secret Mission in Istanbul during the War of the Pacific. The Sale of the Turkish Ironclad Feth-i Bülend (1879-1880) | Paulino Toledo Mansilla

El propósito del autor es abordar la Guerra del Pacífico desde el ángulo de la diplomacia. En particular, el texto se enfoca en las actuaciones del cuerpo diplomático chileno en Europa durante sus dos primeros años. Su tarea: detener los intentos de sus contrincantes, Perú y Bolivia, de obtener apoyos por parte de los gobiernos del Viejo Continente, que habían declarado su neutralidad. Leia Mais

Las desesperantes horas de ocio: tiempo y diversión en Bogotá (1849-1900) | Jorge Humberto Ruiz Patiño

Las transformaciones relacionadas con las fiestas, diversiones y espectáculos en el siglo XIX bogotano dan cuenta de las transformaciones políticas, sociales y urbanísticas de la ciudad. Este postulado se encuentra en la base de la mirada que desarrolla el libro de Jorge Humberto Ruiz, Las desesperantes horas de ocio, tiempo y diversión en Bogotá (1849-1900), investigación que propone una apertura hacia un entendimiento tanto de los procesos políticos como de los fenómenos de sociabilidad que los conforman y acompañan. Leia Mais

Iglesia sin rey. El clero en la independencia neogranadina/1810-1820 | Guillermo Sosa Abella

El libro Iglesia sin rey. El clero en la independencia neogranadina, 1810-1820, de Guillermo Sosa, amplía el espectro de los estudios del hecho religioso en Colombia, al acercarse al sector clerical en el periodo de la Primera República (1810-1815) y en el de Reconquista (1815-1819), protagonizado este último por el general peninsular Pablo Morillo. A diferencia de lo que se ha afirmado como verdad de a puño, Sosa no comulga con la idea de que la revolución de independencia fuera principalmente clerical. De la misma manera, se aparta de aquellos que han visto en los cambios de opinión del clero una postura oportunista. Por el contrario, sostiene que ante la coyuntura política los sacerdotes y los religiosos asumieron una reivindicación corporativa que, más que estar a favor o en contra de la monarquía o la república, centró su foco de interés en sus ingresos, cargos, tribunales, fueros y preeminencias. De esta manera, el autor demuestra que los realistas y los patriotas tenían una misma agenda política con respecto a la Iglesia, por lo que sus miembros lograron acomodarse a las circunstancias sin presentarse como oposición de ninguno de los dos bandos en disputa. En ese sentido, la rebeldía de algunos de sus integrantes más que ir en contravía de la monarquía o la república, se concentró en atacar a las autoridades diocesanas, como lo venían haciendo desde tiempo atrás cuando veían amenazados sus intereses corporativos. Leia Mais

Geel/la città dei matti. L’affidamento familiare dei malati mentali: sette secoli di storia | Renzo Villa

Durante l’acceso dibattito che si svolse, alla fine degli anni Sessanta dell’Ottocento, in seno al Consiglio provinciale di Cuneo per valutare la possibile realizzazione di un manicomio provinciale, si segnalò tra le altre una voce, quella del consigliere Michelini. Liberale e convinto sostenitore dell’idea di nazione, fattosi spesso notare per le chiare posizioni anticlericali1 e per la generosa partecipazione ai moti del 1821 2, il conte avanzò una critica radicale all’idea stessa del manicomio, in quanto luogo d’esclusione. La sua proposta, sviluppata «colla lettera diretta all’egregio dottore Parola»3, era insieme il frutto dell’esperienza di viaggiatore e di un orizzonte mentale aperto e riformista, tanto coraggioso quanto non in linea con le esigenze disciplinari dei tempi. Giovanni Battista Michelini, dopo aver visitato il villaggio belga di Geel, conobbe una modalità diversa di “curare” l’alienazione mentale e la propose alla Commissione Provinciale. Nel villaggio gli alienati soggiornavano presso le famiglie del contado «ove godono d’una libertà che non esclude le cure che esige il loro stato»4. Questa rivoluzione terapeutica aveva raggiunto una certa notorietà nel 1803, quando il prefetto del Dyle aveva deciso, dopo aver preso accordi con le autorità locali, di «trasportare a Geel i pazzi che si custodivano in Bruxelles»5. Esquirol, che visitò il villaggio nel 1821, sostenne che a Geel c’era una colonia di pazzi che si mandano da tutti gli angoli del Dipartimento e dei dipartimenti vicini. Questi infelici sono in pensione presso gli abitanti; passeggiano liberamente nelle contrade, mangiano coi loro ospiti e dormono in loro casa. Se si abbandonano a qualche eccesso, si mette loro dei ferri ai piedi, il che non li trattiene dall’uscire di casa. Questo strano traffico è da tempo immemorabile la sola risorsa degli abitanti di Gheel; non si è mai udito, che ne siano derivati degl’inconvenienti6. Leia Mais

O legado de Marte. olhares múltiplos sobre a Guerra do Paraguai | Marcello José Gomes Loureiro

Marcello José Gomes Loureiro | Imagem: Mondes Americains

Guerras são episódios traumáticos que marcam de maneira indelével países e populações. Por tratar-se do último grande conflito bélico platino e por sua extensão, dramaticidade e sanguinolência, a Guerra do Paraguai marcou a história das Américas. Dela quase todas as quatro nações envolvidas saíram prejudicadas, sobretudo o Paraguai, todas passaram por mudanças, tanto nas relações entre si, quanto nas suas vidas políticas e institucionais internas, e suas populações tiveram as vidas alteradas.

O Brasil não estava preparado para uma guerra de tamanha envergadura como a campanha contra o Paraguai, e teve que mobilizar às pressas a população para constituir um exército, transformando civis em combatentes. Além disto, o governo imperial teve que enfrentar uma série de desafios, militares, diplomáticos e de política interna. Os seis anos do conflito desviaram a atenção do governo das reformas internas; levou a enormes gastos com a luta, gerando um déficit público que persistiu até 1889; explicitou as contradições de uma sociedade que tinha a escravidão como principal instituição; colocou à prova elementos definidores das relações sociais e da cidadania e transformou o exército em importante agente político. Além disto, os historiadores são praticamente unânimes em considerar que a guerra marcou o princípio de erosão do sistema monárquico. Leia Mais

Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching | Jarvis R. Givens

Jarvis R. Givens | Imagens: The Black Teacher Archive

Born in 1865 during the last years of the American Civil War, Carter H. Barnett was a teacher and the principal of Frederick Douglass School in Huntington, West Virginia, where he edited the West Virginia Spokesman and contributed to the state’s Black teacher association. Positioned on the edge of a tattered 1896 photograph, he stands to the right of fifty-some school children assembled in motley garb on the school steps, Garnett’s own studious dress and the hat held in his hand testament to his status as Principal of this six-room school.

In 1900 Garnett was fired after he alienated local white leaders by proposing a series of Black candidates for political office who were independent from the local Republican Party. His replacement, the beneficiary of the persistent vulnerability of Black educators and—likely unbeknownst to the white school board—his cousin, was Carter G. Woodson, now well-known and indeed lionized as the ‘Father of Black History Month.’ Barnett’s story is a particularly resonant instance of the many under-examined stories unearthed in Jarvis Givens’s Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching. Utilising Woodson as a centripetal focus, Givens unveils the full tapestry of Black education life, juxtaposing the fortunes and misfortunes of a realm “always in crisis; always teetering between strife and hope and prayer” (p. 22).

Givens, an assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, maps this liminal position by excavating a pedagogical heritage of ‘fugitivity’, following the insights of theorists including Édouard Glissant, Saidiya Hartman, and Nathaniel Mackey. Invoking Mackey’s conception of the “fugitive spirit” of Black social life more broadly (p. vii), Fugitive Pedagogy describes the everyday acts of subversion Black teachers employed to teach students about Black history and heritage amid “persistent discursive and physical assaults.” (p 34). As Givens takes pains to emphasise, these acts were not isolated episodes but instead “the occasion, the main event”, representing the visible aspects of an “overarching set of political commitments” that dated to the period of enslavement and continued to be anchored in celebrations of the folk heroism of the fugitive slave (p. 16). The fugitive slave’s example symbolised a space of existence outside of prescribed racial orders, where African Americans could collectively assert their capacity to be educated, rational, and human. In the words of Master Hugh from The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, a slave who knew how to write was “running away with himself” (p. 12).

A great strength of this analytic, as opposed to resistance or freedom, is to emphasise that Black educational efforts were always fated to struggle against centuries of legislation and beliefs that denied Black educability. Incorporating Achille Mbembe’s Critique of Black Reason, Givens suggests that this “chattel principle” that rendered African-descended peoples fungible property to be exchanged by slaveholders denied their potential rationality, catalysing subsequent antiliteracy laws (p. 10). Slaves were to have “only hands, not heads”, hence the declaration of legislation following 1739’s Stono Rebellion that “the having of slaves taught to write, or suffering them to be employed in writing, may be attended with great inconveniences” (p. 11). Locating Black educators in the ‘Afterlives of Slavery’, Givens thus suggests that to be Black and educated has always represented “an insistence on Black living, even amid the perpetual threat of Black social death” (p. 10).

Fugitivity also voices the affective and embodied natures of teaching, where classrooms underwent “aesthetic transformation… to defy the normative protocols of the American School” (p. 204). For Givens, education is corporeal, embodied, and freighted with emotional resonance, its putative impossibility under dominant racial scripts “etched into Black flesh” (p. 20). Conversely, miseducation and antiblack curricular violence are situated as symbiotic with physical violence, hence the frequent quotation of Woodson’s assertion “there would be no lynching if it did not start in the schoolroom.” (pp. 95-96). Thematically, Givens thus emphasises Black education as a learning experience, something recovered by trawling a “patchwork of sources” from a diverse archive to privilege the often understudied experiences of Black students themselves and uncovering that common contradiction between “what they said or wrote” (p. 20).

Givens’s “collage of fugitive pedagogy” (p. 24) is constellated around the “particular, emblematic narrative” (p. 4) of Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950), the author, historian, and founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). As opposed to echoing Jacqueline Goggin and Pero Galgo Dagbovie’s accomplished biographies of Woodson, Fugitive Pedagogy analyses Woodson in constant relation to the ASALH’s broader network of scholars to demonstrate how Woodson “inherited a tradition and then played a crucial role in expanding it” (p. 16). (1) By effectively dethroning Woodson, this networked approach paints a more expansive portrait than the patrilineal tendency to centre the individual achievements of this ‘father’ of Black Studies.

For example, Givens’s first chapter provides a fresh perspective on the already well-examined subject of Woodson’s life from 1875-1912 by emphasising his socialization into a vibrant pre-existing “black educational world” (p. 26). This deliberately privileges Woodson the teacher over Woodson the later scholar, highlighting how reading newspapers to the Civil War veterans he worked alongside in West Virginia’s coal mines and witnessing his teachers, frequently themselves formerly enslaved men, allowed Woodson to develop “a studied perspective on the distinct vocational demands of being a black teacher” (p. 26). Taking Woodson as emblematic of the first post-emancipation school generation thus stresses the continuities in Black education’s striving against a pre and post-emancipation antiblack social order, revealing how teaching the formerly enslaved consequently remained “an act of unmaking the terms of their relation to the word and world” (p. 35).

Chapter Two highlights how Woodson’s desire to denaturalize prevailing forms of scientific judgement found an “institutional embodiment” in the ASALH, one instance of Woodson’s wider designs to form a Black “counterpublic” (p. 71). Whilst this is also well-trodden ground, the fugitive pedagogy motif nonetheless helps to explain the Association’s shift from the interracial historical alliance conceptualized in 1915 to its more polemic form in the 1930s. This was, Givens argues, a direct response to the epistemological violence of racist films such as Birth of the Nation and the physical violence of contemporary race riots such as 1919’s ‘Red Summer.’ In a position of eternal vigilance, the Association was thus portrayed “standing like the watchman on the wall, ever mindful of what calamities we have suffered from misinterpretation in the past and looking out with a scrutinizing eye for everything indicative of a similar attack” (p. 62).

Chapter Three moves to embed Woodson in a distinct tradition of Black educational thought, a literature of educational criticism that sought to counter the disfiguring of Black knowledge within American public life. As opposed to emphasising the barriers preventing access into American schools and universities, Givens instead underscores the “epistemological underpinnings of education provided to those who made it past these barriers” (p. 97). Thus, Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro (1933) critiqued the “imitation resulting in the enslavement of his mind”, particularly from institutions like Harvard which rendered its students “blind to the Negro” and unable to “serve the race efficiently” (pp. 98-99). In the most theoretically expansive section of Fugitive Pedagogy, Givens articulates this Woodsonian critique of pedagogical ‘mimicry’ to the adjacent conceptions of several extra-American Black thinkers regarding the disfiguring of Black knowledge: Aimé Césaire’s ‘thingification’, Sylvia Wynter’s ‘narrative condemnation’, and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o’s ‘cultural bomb.’

Chapter Four too ballasts fugitive pedagogy in the remembrance of the Black fugitive as an “an archetype who symbolized Black people’s political relationship to the modern world and its technologies of schooling” (p. 128). This archetype indicates the wider use of Black historical achievements as models for present political action within textbooks that sought to vindicate Black intellectual and political life by recalling the full history of resistance within the Black diaspora. In this sense, Givens concludes, the Black textbook was “itself a literary genre inaugurated by runaway slaves” (p. 158). This tradition rendered curricular violence visible, distilling the possibility of resistance by evoking a Black aesthetic that situated subversion and defiance as long-standing threads of Black existence.

Chapter Five looks to connect Woodson to a cadre of Black schoolteachers. Adapting the term “abroad marriages”, originally applied to those enslaved who married those living on different plantations, Givens shows how Woodson the ‘abroad mentor’ utilised the Black press, the ASALH, and particularly Negro History Week to translate his ideas to school teachers, pausing along the way to examine the inequity in school provision and the restrictions on teaching they faced, particularly in the South. One notable example was the Negro Manual and Training High School in Muskogee, Oklahoma. In 1925 its Principal Thomas W. Grissom was forced to resign after officials found Woodson’s The Negro in Our History being taught, with the school board decreeing that nothing could be “instilled in the schools that is either klan or antiklan” (p. 168).

Finally, Chapter Six looks to centre students as “partners in [the] performance of fugitive pedagogy” by analysing biographical materials recounting the school days of prominent civil rights activists, politicians, and scholars including Angela Davis, John Lewis, and John Bracey (p. 199). Whilst subsequent activists are likely to be far from representative, Givens effectively emphasises the aesthetic ecology of the classroom and how the value systems undergirding school routines, rules, and projects including Negro History Week “inducted [students] as neophytes in a continuum of consciousness” (p. 222). This collection of visual narratives, Givens argues, formed an ‘oppositional gaze’, a disposition to question social technologies that perpetuated antiblack violence. The example of Congressman John Lewis is particularly resonant, as Givens shows Lewis prefiguring his later contribution to the sit-in movement by asking a public library in Troy, Alabama for library cards for him, his siblings, and his cousins despite their full awareness of the futility of this request.

If Fugitive Pedagogy has one weakness, it is the underplaying of intraracial differences inevitable within Givens’s artifice. Whilst Givens stresses that fugitivity is a variable practice, he asserts that “surely there are deviations, but they are not the concern here” (p. 16). Correspondingly, Fugitive Pedagogy makes no attempt to comprehensively trace variations in region, class, and gender. In a book of just over 300 pages, this is a pragmatic decision which avoids diluting the argumentative thrust. Yet consequential statements of intraracial equality are on occasion made rather too briefly. For example, Givens looks to identify the ASALH as “an intellectual project with Black Americans across age, class, and gender in mind,” defining his inclusion of gender here as a “careful assertion” (p. 84). Granted, Givens effectively illustrates that Black women consistently made up more than three-quarters of the profession and rose to prominent positions, with Mary McLeod Bethune becoming the ASALH’s President from 1936 to 1951. Yet this is not to say that Black women’s contributions were adequately recognised or recompensed, particularly given Patrice Morton’s suggestion that the ASALH failed to challenge many myths of Black womanhood prior to the late 20th century.(2)

Second, further research is needed to layer fugitive pedagogy into the full scope of Black institutional life, investigating how fugitive pedagogy translated to ancillary sites of education, including clubs, sporting societies, libraries, and churches. Givens consciously distances his argument from quantitative assessments of the inequality of educational provision yet this risks obscuring regional variations in resources and the vital ties between low wages, economic precarity, and professional vulnerability. Fugitive Pedagogy largely develops ‘upwards’ from individual acts of fugitivity, occasionally de-emphasising the institutional context. This means that readers hear little about mundane but vital factors including roofs, heating, lighting, desks, school grounds, teacher-pupil ratios, or the disproportionate private ownership of Black schools. With the firings of both Grissom and Barnett, Givens correspondingly emphasises the outcome rather than the process, occluding the logics and justifications of school boards and the pressures placed upon them by local (white) communities. Should an adequate archive exist, an ecological study focused on fugitive pedagogy within a single school would particularly flesh out Givens’s framework.

Third, given the roots of fugitive pedagogy in the discrete experience and memories of slavery, could other insurgent pedagogies employ fugitive practices? If not, there is a risk that the fugitive model shifts a further emotive and educative burden to Black teachers, compounding the long-standing tendency already recognised by Givens for Black teachers to double tax themselves to achieve liberatory ends. Givens suggests so, situating Black fugitive pedagogy as one discrete tradition within a broader genre of educational criticism that critiqued orthodox models of schooling, a purposive attempt to “leave room to consider… bodies of educational criticism by Native American educators and thinkers, Marxist educators, and feminist teachers and thinkers, among others who understand their political motivations for teaching to be in direct tension with the protocols and dominant ideology of the American school” (p. 251, cf.76). Further, recounting recorded acts of fugitivity necessarily underplays the longer slog of merely existing and making a living within white institutions, with all the undoubtedly uneasy cross-racial cooperation and interest convergence this entailed. When reckoning with this subject matter, any historian is condemned to see only the tip of the iceberg, only those acts visible in the archive through exorbitant chance and, more than often than not, only when refracted through the institutional memory of surveillance institutions. Whilst Givens has collected a vast archive of Black voices, there remains the risk of privileging more palpable disobedience over the dissemblances and circumlocutions which could allow Black teachers “wearing the mask” to articulate an activist ethos within the confines of objectivity.

These three areas for further investigation notwithstanding, Fugitive Pedagogy ultimately offers an engrossing reminder of the importance of collective education that is particularly resonant in the world of individualised algorithmic learning that followed the COVID-19 pandemic. Ambitious and theoretically virtuosic in exposition, magnetic and energizing in execution, the clarity of its theoretical interventions suggests that its broad brushstrokes will be imminently nuanced by other scholars empowered by the fugitive framework and its relevance to current pedagogical debates.

As the February 2022 victory of a diverse coalition against Indiana’s House Bill 1134 signals a growing resistance to anti-CRT legislation, Givens is particularly commendable for his insistence on Black education’s prescriptive moral force. A more diluted ‘anti-racist’ pedagogy within contemporary education that often tends towards the personal and psychological, towards diversity and inclusion, is cut short shrift compared to a progressive pedagogy that acknowledges the structural determinants of white supremacy. For Givens, education provides an alternative prospectus for living. If this may appear somewhat utopian, Fugitive Pedagogy at least provides a powerful argument for cross-professional solidarity between academia and schoolteachers. This will undoubtedly be furthered by Givens’s creation (alongside Princeton’s Imani Perry) of the Black Teacher Archives. As Givens notes, this disposition represents “an international refusal of contemporary trends where teachers are deprofessionalized in general and where black teachers in particular have been systemically alienated, often being positioned as unintellectual and nonpedagogical knowers” (p. 239).

Excavating Black education’s persistent fugitive ethos also emphasises that the ‘political’ education challenged by recent anti-CRT laws has only been rendered visible and legislatively-eradicable in proportion to white discomfort. Historicizing this ethos thus provides a warning against retreating to political ‘neutrality’ as such an option has never existed. Ultimately, Fugitive Pedagogy suggests that any pedagogy seeking to advance Black achievement is necessarily ‘political’, if only because the mere social fact of Black literacy confounds the founding principles of the American Republic.

To be sure, teachers in the present United States face their own dilemmas. Contemporary educators face not only an onslaught of anti-CRT legislation but also the dilemmas of retaining any activist impulse behind Black education within a racial liberalism that stresses the integration of Black history into multi-racial educational programmes disarticulated from the Black counterpublic sphere. As Givens recently recognised in The Los Angeles Review of Books: “We must also recognize… that [the] siloed inclusion of Black knowledge into mainstream institutions- often in defanged fashion- can only do so much to disrupt the self-corrective nature of said systems.” (3)

Jarvis Givens’s Fugitive Pedagogy places educational strivings at the heart of the Black freedom struggle, providing historians of the United States a digestible testament to the methodological interventions and activist orientations of recent historians of Black education. Suitable for both advanced undergraduates and the public, Givens’s work deserves a central role in syllabuses on the Black freedom struggle, the sociology of knowledge, and broader histories of resistance to educational domination. As the global education sector rebuilds following COVID-19, Fugitive Pedagogy cogently conveys this literature’s overwhelming emphasis on the virtues of disciplinary self-introspection and recovering shared professional heritages. If much of the fugitive tradition with its attendant varieties remains to be fully pieced out, Givens nonetheless articulates a grammar for struggle that can provide refortification to our own generation’s embattled teachers who choose to think otherwise. Teetering once more between “strife and hope and prayer”, Fugitive Pedagogy articulates a language that provides historical ballast for the present and argumentative weapons for the future.

Thomas Cryer (he/him) is a first-year AHRC-funded PhD student at University College London’s Institute of the Americas, where he studies memory, race, and, nationhood in the late-20th-century United States through the lens of the life, scholarship, and activism of the historian John Hope Franklin. [Twitter: @ThomasOCryer]

Notes

1 Pero Gaglo Dagbovie, The Early Black History Movement, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007) & Jacqueline Anne Goggin, Carter G. Woodson: A Life in Black History, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993).Back to (1)

2 Patricia Morton, Disfigured Images: The Historical Assault on Afro-American Women, (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991).Back to (2)

3 Jarvis Givens, ‘Fugitive Pedagogy: The Longer Roots of Antiracist Teaching,’ The LA Review of Books, August 18th, 2021.Back to (3)

Resenhista

Thomas Cryer - University College London.

Referências desta Resenha

GIVENS, Jarvis R. Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021. Resenha de: CRYER, Thomas. Reviews in History. Londres, n. 2465, sep. 2022. Acessar publicação original [DR]

Givens, an assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, maps this liminal position by excavating a pedagogical heritage of ‘fugitivity’, following the insights of theorists including Édouard Glissant, Saidiya Hartman, and Nathaniel Mackey. Invoking Mackey’s conception of the “fugitive spirit” of Black social life more broadly (p. vii), Fugitive Pedagogy describes the everyday acts of subversion Black teachers employed to teach students about Black history and heritage amid “persistent discursive and physical assaults.” (p 34). As Givens takes pains to emphasise, these acts were not isolated episodes but instead “the occasion, the main event”, representing the visible aspects of an “overarching set of political commitments” that dated to the period of enslavement and continued to be anchored in celebrations of the folk heroism of the fugitive slave (p. 16). The fugitive slave’s example symbolised a space of existence outside of prescribed racial orders, where African Americans could collectively assert their capacity to be educated, rational, and human. In the words of Master Hugh from The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, a slave who knew how to write was “running away with himself” (p. 12).

A great strength of this analytic, as opposed to resistance or freedom, is to emphasise that Black educational efforts were always fated to struggle against centuries of legislation and beliefs that denied Black educability. Incorporating Achille Mbembe’s Critique of Black Reason, Givens suggests that this “chattel principle” that rendered African-descended peoples fungible property to be exchanged by slaveholders denied their potential rationality, catalysing subsequent antiliteracy laws (p. 10). Slaves were to have “only hands, not heads”, hence the declaration of legislation following 1739’s Stono Rebellion that “the having of slaves taught to write, or suffering them to be employed in writing, may be attended with great inconveniences” (p. 11). Locating Black educators in the ‘Afterlives of Slavery’, Givens thus suggests that to be Black and educated has always represented “an insistence on Black living, even amid the perpetual threat of Black social death” (p. 10).

Fugitivity also voices the affective and embodied natures of teaching, where classrooms underwent “aesthetic transformation… to defy the normative protocols of the American School” (p. 204). For Givens, education is corporeal, embodied, and freighted with emotional resonance, its putative impossibility under dominant racial scripts “etched into Black flesh” (p. 20). Conversely, miseducation and antiblack curricular violence are situated as symbiotic with physical violence, hence the frequent quotation of Woodson’s assertion “there would be no lynching if it did not start in the schoolroom.” (pp. 95-96). Thematically, Givens thus emphasises Black education as a learning experience, something recovered by trawling a “patchwork of sources” from a diverse archive to privilege the often understudied experiences of Black students themselves and uncovering that common contradiction between “what they said or wrote” (p. 20).

Givens’s “collage of fugitive pedagogy” (p. 24) is constellated around the “particular, emblematic narrative” (p. 4) of Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950), the author, historian, and founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). As opposed to echoing Jacqueline Goggin and Pero Galgo Dagbovie’s accomplished biographies of Woodson, Fugitive Pedagogy analyses Woodson in constant relation to the ASALH’s broader network of scholars to demonstrate how Woodson “inherited a tradition and then played a crucial role in expanding it” (p. 16). (1) By effectively dethroning Woodson, this networked approach paints a more expansive portrait than the patrilineal tendency to centre the individual achievements of this ‘father’ of Black Studies.

For example, Givens’s first chapter provides a fresh perspective on the already well-examined subject of Woodson’s life from 1875-1912 by emphasising his socialization into a vibrant pre-existing “black educational world” (p. 26). This deliberately privileges Woodson the teacher over Woodson the later scholar, highlighting how reading newspapers to the Civil War veterans he worked alongside in West Virginia’s coal mines and witnessing his teachers, frequently themselves formerly enslaved men, allowed Woodson to develop “a studied perspective on the distinct vocational demands of being a black teacher” (p. 26). Taking Woodson as emblematic of the first post-emancipation school generation thus stresses the continuities in Black education’s striving against a pre and post-emancipation antiblack social order, revealing how teaching the formerly enslaved consequently remained “an act of unmaking the terms of their relation to the word and world” (p. 35).

Chapter Two highlights how Woodson’s desire to denaturalize prevailing forms of scientific judgement found an “institutional embodiment” in the ASALH, one instance of Woodson’s wider designs to form a Black “counterpublic” (p. 71). Whilst this is also well-trodden ground, the fugitive pedagogy motif nonetheless helps to explain the Association’s shift from the interracial historical alliance conceptualized in 1915 to its more polemic form in the 1930s. This was, Givens argues, a direct response to the epistemological violence of racist films such as Birth of the Nation and the physical violence of contemporary race riots such as 1919’s ‘Red Summer.’ In a position of eternal vigilance, the Association was thus portrayed “standing like the watchman on the wall, ever mindful of what calamities we have suffered from misinterpretation in the past and looking out with a scrutinizing eye for everything indicative of a similar attack” (p. 62).

Chapter Three moves to embed Woodson in a distinct tradition of Black educational thought, a literature of educational criticism that sought to counter the disfiguring of Black knowledge within American public life. As opposed to emphasising the barriers preventing access into American schools and universities, Givens instead underscores the “epistemological underpinnings of education provided to those who made it past these barriers” (p. 97). Thus, Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro (1933) critiqued the “imitation resulting in the enslavement of his mind”, particularly from institutions like Harvard which rendered its students “blind to the Negro” and unable to “serve the race efficiently” (pp. 98-99). In the most theoretically expansive section of Fugitive Pedagogy, Givens articulates this Woodsonian critique of pedagogical ‘mimicry’ to the adjacent conceptions of several extra-American Black thinkers regarding the disfiguring of Black knowledge: Aimé Césaire’s ‘thingification’, Sylvia Wynter’s ‘narrative condemnation’, and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o’s ‘cultural bomb.’

Chapter Four too ballasts fugitive pedagogy in the remembrance of the Black fugitive as an “an archetype who symbolized Black people’s political relationship to the modern world and its technologies of schooling” (p. 128). This archetype indicates the wider use of Black historical achievements as models for present political action within textbooks that sought to vindicate Black intellectual and political life by recalling the full history of resistance within the Black diaspora. In this sense, Givens concludes, the Black textbook was “itself a literary genre inaugurated by runaway slaves” (p. 158). This tradition rendered curricular violence visible, distilling the possibility of resistance by evoking a Black aesthetic that situated subversion and defiance as long-standing threads of Black existence.

Chapter Five looks to connect Woodson to a cadre of Black schoolteachers. Adapting the term “abroad marriages”, originally applied to those enslaved who married those living on different plantations, Givens shows how Woodson the ‘abroad mentor’ utilised the Black press, the ASALH, and particularly Negro History Week to translate his ideas to school teachers, pausing along the way to examine the inequity in school provision and the restrictions on teaching they faced, particularly in the South. One notable example was the Negro Manual and Training High School in Muskogee, Oklahoma. In 1925 its Principal Thomas W. Grissom was forced to resign after officials found Woodson’s The Negro in Our History being taught, with the school board decreeing that nothing could be “instilled in the schools that is either klan or antiklan” (p. 168).

Finally, Chapter Six looks to centre students as “partners in [the] performance of fugitive pedagogy” by analysing biographical materials recounting the school days of prominent civil rights activists, politicians, and scholars including Angela Davis, John Lewis, and John Bracey (p. 199). Whilst subsequent activists are likely to be far from representative, Givens effectively emphasises the aesthetic ecology of the classroom and how the value systems undergirding school routines, rules, and projects including Negro History Week “inducted [students] as neophytes in a continuum of consciousness” (p. 222). This collection of visual narratives, Givens argues, formed an ‘oppositional gaze’, a disposition to question social technologies that perpetuated antiblack violence. The example of Congressman John Lewis is particularly resonant, as Givens shows Lewis prefiguring his later contribution to the sit-in movement by asking a public library in Troy, Alabama for library cards for him, his siblings, and his cousins despite their full awareness of the futility of this request.

If Fugitive Pedagogy has one weakness, it is the underplaying of intraracial differences inevitable within Givens’s artifice. Whilst Givens stresses that fugitivity is a variable practice, he asserts that “surely there are deviations, but they are not the concern here” (p. 16). Correspondingly, Fugitive Pedagogy makes no attempt to comprehensively trace variations in region, class, and gender. In a book of just over 300 pages, this is a pragmatic decision which avoids diluting the argumentative thrust. Yet consequential statements of intraracial equality are on occasion made rather too briefly. For example, Givens looks to identify the ASALH as “an intellectual project with Black Americans across age, class, and gender in mind,” defining his inclusion of gender here as a “careful assertion” (p. 84). Granted, Givens effectively illustrates that Black women consistently made up more than three-quarters of the profession and rose to prominent positions, with Mary McLeod Bethune becoming the ASALH’s President from 1936 to 1951. Yet this is not to say that Black women’s contributions were adequately recognised or recompensed, particularly given Patrice Morton’s suggestion that the ASALH failed to challenge many myths of Black womanhood prior to the late 20th century.(2)

Second, further research is needed to layer fugitive pedagogy into the full scope of Black institutional life, investigating how fugitive pedagogy translated to ancillary sites of education, including clubs, sporting societies, libraries, and churches. Givens consciously distances his argument from quantitative assessments of the inequality of educational provision yet this risks obscuring regional variations in resources and the vital ties between low wages, economic precarity, and professional vulnerability. Fugitive Pedagogy largely develops ‘upwards’ from individual acts of fugitivity, occasionally de-emphasising the institutional context. This means that readers hear little about mundane but vital factors including roofs, heating, lighting, desks, school grounds, teacher-pupil ratios, or the disproportionate private ownership of Black schools. With the firings of both Grissom and Barnett, Givens correspondingly emphasises the outcome rather than the process, occluding the logics and justifications of school boards and the pressures placed upon them by local (white) communities. Should an adequate archive exist, an ecological study focused on fugitive pedagogy within a single school would particularly flesh out Givens’s framework.

Third, given the roots of fugitive pedagogy in the discrete experience and memories of slavery, could other insurgent pedagogies employ fugitive practices? If not, there is a risk that the fugitive model shifts a further emotive and educative burden to Black teachers, compounding the long-standing tendency already recognised by Givens for Black teachers to double tax themselves to achieve liberatory ends. Givens suggests so, situating Black fugitive pedagogy as one discrete tradition within a broader genre of educational criticism that critiqued orthodox models of schooling, a purposive attempt to “leave room to consider… bodies of educational criticism by Native American educators and thinkers, Marxist educators, and feminist teachers and thinkers, among others who understand their political motivations for teaching to be in direct tension with the protocols and dominant ideology of the American school” (p. 251, cf.76). Further, recounting recorded acts of fugitivity necessarily underplays the longer slog of merely existing and making a living within white institutions, with all the undoubtedly uneasy cross-racial cooperation and interest convergence this entailed. When reckoning with this subject matter, any historian is condemned to see only the tip of the iceberg, only those acts visible in the archive through exorbitant chance and, more than often than not, only when refracted through the institutional memory of surveillance institutions. Whilst Givens has collected a vast archive of Black voices, there remains the risk of privileging more palpable disobedience over the dissemblances and circumlocutions which could allow Black teachers “wearing the mask” to articulate an activist ethos within the confines of objectivity.

These three areas for further investigation notwithstanding, Fugitive Pedagogy ultimately offers an engrossing reminder of the importance of collective education that is particularly resonant in the world of individualised algorithmic learning that followed the COVID-19 pandemic. Ambitious and theoretically virtuosic in exposition, magnetic and energizing in execution, the clarity of its theoretical interventions suggests that its broad brushstrokes will be imminently nuanced by other scholars empowered by the fugitive framework and its relevance to current pedagogical debates.

As the February 2022 victory of a diverse coalition against Indiana’s House Bill 1134 signals a growing resistance to anti-CRT legislation, Givens is particularly commendable for his insistence on Black education’s prescriptive moral force. A more diluted ‘anti-racist’ pedagogy within contemporary education that often tends towards the personal and psychological, towards diversity and inclusion, is cut short shrift compared to a progressive pedagogy that acknowledges the structural determinants of white supremacy. For Givens, education provides an alternative prospectus for living. If this may appear somewhat utopian, Fugitive Pedagogy at least provides a powerful argument for cross-professional solidarity between academia and schoolteachers. This will undoubtedly be furthered by Givens’s creation (alongside Princeton’s Imani Perry) of the Black Teacher Archives. As Givens notes, this disposition represents “an international refusal of contemporary trends where teachers are deprofessionalized in general and where black teachers in particular have been systemically alienated, often being positioned as unintellectual and nonpedagogical knowers” (p. 239).

Excavating Black education’s persistent fugitive ethos also emphasises that the ‘political’ education challenged by recent anti-CRT laws has only been rendered visible and legislatively-eradicable in proportion to white discomfort. Historicizing this ethos thus provides a warning against retreating to political ‘neutrality’ as such an option has never existed. Ultimately, Fugitive Pedagogy suggests that any pedagogy seeking to advance Black achievement is necessarily ‘political’, if only because the mere social fact of Black literacy confounds the founding principles of the American Republic.

To be sure, teachers in the present United States face their own dilemmas. Contemporary educators face not only an onslaught of anti-CRT legislation but also the dilemmas of retaining any activist impulse behind Black education within a racial liberalism that stresses the integration of Black history into multi-racial educational programmes disarticulated from the Black counterpublic sphere. As Givens recently recognised in The Los Angeles Review of Books: “We must also recognize… that [the] siloed inclusion of Black knowledge into mainstream institutions- often in defanged fashion- can only do so much to disrupt the self-corrective nature of said systems.” (3)

Jarvis Givens’s Fugitive Pedagogy places educational strivings at the heart of the Black freedom struggle, providing historians of the United States a digestible testament to the methodological interventions and activist orientations of recent historians of Black education. Suitable for both advanced undergraduates and the public, Givens’s work deserves a central role in syllabuses on the Black freedom struggle, the sociology of knowledge, and broader histories of resistance to educational domination. As the global education sector rebuilds following COVID-19, Fugitive Pedagogy cogently conveys this literature’s overwhelming emphasis on the virtues of disciplinary self-introspection and recovering shared professional heritages. If much of the fugitive tradition with its attendant varieties remains to be fully pieced out, Givens nonetheless articulates a grammar for struggle that can provide refortification to our own generation’s embattled teachers who choose to think otherwise. Teetering once more between “strife and hope and prayer”, Fugitive Pedagogy articulates a language that provides historical ballast for the present and argumentative weapons for the future.

Thomas Cryer (he/him) is a first-year AHRC-funded PhD student at University College London’s Institute of the Americas, where he studies memory, race, and, nationhood in the late-20th-century United States through the lens of the life, scholarship, and activism of the historian John Hope Franklin. [Twitter: @ThomasOCryer]

Notes

1 Pero Gaglo Dagbovie, The Early Black History Movement, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007) & Jacqueline Anne Goggin, Carter G. Woodson: A Life in Black History, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993).Back to (1)

2 Patricia Morton, Disfigured Images: The Historical Assault on Afro-American Women, (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991).Back to (2)

3 Jarvis Givens, ‘Fugitive Pedagogy: The Longer Roots of Antiracist Teaching,’ The LA Review of Books, August 18th, 2021.Back to (3)

Resenhista

Thomas Cryer - University College London.

Referências desta Resenha

GIVENS, Jarvis R. Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021. Resenha de: CRYER, Thomas. Reviews in History. Londres, n. 2465, sep. 2022. Acessar publicação original [DR]

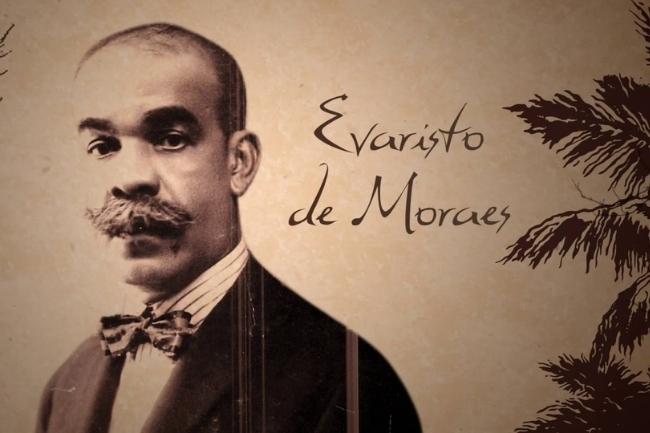

À época da escrita desse livro, Evaristo de Morais era um jovem abolicionista, jornalista, advogado e professor que, aos dezesseis anos de idade, esteve presente nas comemorações alusivas à assinatura da Lei Aurea, pela princesa regente, Isabel de Bragança. Nascido na cidade do Rio de Janeiro, em 26 de outubro de 1871, o mulato era (para os padrões da época) pertencente a uma família de classe média. Nos primeiros anos da vida escolar, Moraes estudou no Colégio de São Bento e foi aluno dos notáveis Clóvis Bevilaqua, Tobias Barreto, Sílvio Romero, Artur Orlando da Silva, dentre outros. Em 1888, já era professor de português, jornalista e abolicionista.

À época da escrita desse livro, Evaristo de Morais era um jovem abolicionista, jornalista, advogado e professor que, aos dezesseis anos de idade, esteve presente nas comemorações alusivas à assinatura da Lei Aurea, pela princesa regente, Isabel de Bragança. Nascido na cidade do Rio de Janeiro, em 26 de outubro de 1871, o mulato era (para os padrões da época) pertencente a uma família de classe média. Nos primeiros anos da vida escolar, Moraes estudou no Colégio de São Bento e foi aluno dos notáveis Clóvis Bevilaqua, Tobias Barreto, Sílvio Romero, Artur Orlando da Silva, dentre outros. Em 1888, já era professor de português, jornalista e abolicionista.

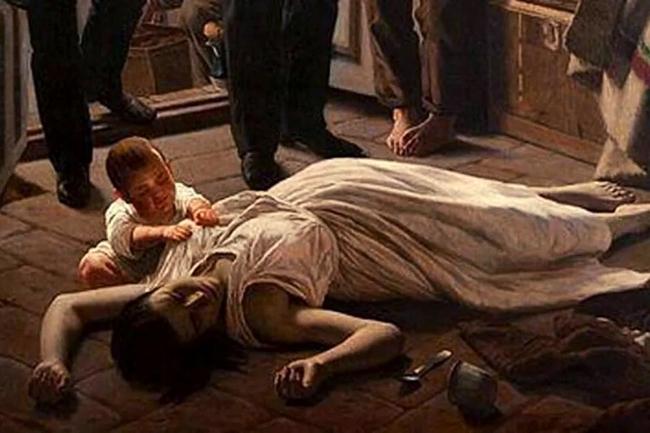

Muito se discute atualmente sobre o papel do Poder Judiciário no Brasil. Em fins do século XIX, permearam as instâncias e as decisões judiciais ações cíveis cujo objeto era a liberdade de escravos. Sem os meios de comunicação de que hoje dispomos, ainda assim parte da sociedade estava atenta ao assunto. Para além da opinião pública e dos movimentos sociais de então, o trabalho que temos em mãos tem como ponto de partida um elemento bastante presente nas fontes utilizadas para o estudo da escravidão, mas nem sempre em evidência nas investigações relacionadas ao tema: o Estado. De que modo os agentes atuantes na estrutura judiciária do Império lidaram com os processos impetrados pela liberdade de homens e mulheres na condição de escravos? Que instrumental advogados e desembargadores operaram em suas argumentações e decisões?

Muito se discute atualmente sobre o papel do Poder Judiciário no Brasil. Em fins do século XIX, permearam as instâncias e as decisões judiciais ações cíveis cujo objeto era a liberdade de escravos. Sem os meios de comunicação de que hoje dispomos, ainda assim parte da sociedade estava atenta ao assunto. Para além da opinião pública e dos movimentos sociais de então, o trabalho que temos em mãos tem como ponto de partida um elemento bastante presente nas fontes utilizadas para o estudo da escravidão, mas nem sempre em evidência nas investigações relacionadas ao tema: o Estado. De que modo os agentes atuantes na estrutura judiciária do Império lidaram com os processos impetrados pela liberdade de homens e mulheres na condição de escravos? Que instrumental advogados e desembargadores operaram em suas argumentações e decisões?

Neste livro, Wilson González Demuro analisa o papel da imprensa na criação de um espaço moderno de opinião pública em Montevidéu, integrado ao processo de desconstrução do Antigo Regime na América por suas independências e construção de Estados nacionais, assentados em governos representativos, baseados princípios liberais.

Neste livro, Wilson González Demuro analisa o papel da imprensa na criação de um espaço moderno de opinião pública em Montevidéu, integrado ao processo de desconstrução do Antigo Regime na América por suas independências e construção de Estados nacionais, assentados em governos representativos, baseados princípios liberais.

O livro da historiadora Andrea Reguera analisa a construção do poder de Juan Manuel de Rosas a partir da trama de relações interpessoais que atravessaram sua vida e a política adotada entre 1829-1833 e 1835-1852, quando assumiu o cargo de governador da província de Buenos Aires após ser eleito pela Sala de Representantes nos dois períodos. Utilizando-se, principalmente, de correspondências pessoais de Rosas, Reguera destaca a busca pela subjetividade do indivíduo na construção das relações constitutivas e dissolutivas a fim de compreender o jogo de poder presente nelas e os limites entre o público e o privado.

O livro da historiadora Andrea Reguera analisa a construção do poder de Juan Manuel de Rosas a partir da trama de relações interpessoais que atravessaram sua vida e a política adotada entre 1829-1833 e 1835-1852, quando assumiu o cargo de governador da província de Buenos Aires após ser eleito pela Sala de Representantes nos dois períodos. Utilizando-se, principalmente, de correspondências pessoais de Rosas, Reguera destaca a busca pela subjetividade do indivíduo na construção das relações constitutivas e dissolutivas a fim de compreender o jogo de poder presente nelas e os limites entre o público e o privado.

“As principais famílias charqueadoras do período escravista foram capazes de criar um mundo próprio e fizeram da cidade de Pelotas o seu palco particular. Neste cenário, o acesso às artes, à educação superior e à liderança política coube a elas e a algumas outras famílias da elite local” (Vargas, 2016, p.317) O cantor e compositor Vitor Ramil, certa feita, disse ter “convicção que o Rio Grande do Sul não estava à margem do centro do Brasil, mas sim no centro de uma outra história”. Ramil, que é pelotense, certamente formulou essa opinião tendo como inspiração a sua amada cidade natal, que a retrata de modo idealista, ou realista, como Satolep. Pois essa Pelotas centro de uma outra história é a encontrada no profundo trabalho escrito pelo historiador e professor do curso de História da UFPel, Jonas Vargas.

“As principais famílias charqueadoras do período escravista foram capazes de criar um mundo próprio e fizeram da cidade de Pelotas o seu palco particular. Neste cenário, o acesso às artes, à educação superior e à liderança política coube a elas e a algumas outras famílias da elite local” (Vargas, 2016, p.317) O cantor e compositor Vitor Ramil, certa feita, disse ter “convicção que o Rio Grande do Sul não estava à margem do centro do Brasil, mas sim no centro de uma outra história”. Ramil, que é pelotense, certamente formulou essa opinião tendo como inspiração a sua amada cidade natal, que a retrata de modo idealista, ou realista, como Satolep. Pois essa Pelotas centro de uma outra história é a encontrada no profundo trabalho escrito pelo historiador e professor do curso de História da UFPel, Jonas Vargas.

David F. L. Gomes é professor efetivo da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG) e possui longa trajetória de pesquisa nas áreas de Teoria da Constituição, Teoria do Estado, Sociologia e História do Direito.

David F. L. Gomes é professor efetivo da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG) e possui longa trajetória de pesquisa nas áreas de Teoria da Constituição, Teoria do Estado, Sociologia e História do Direito.

Introdução

Introdução

O livro de Keith Valéria de Oliveira Barbosa, pesquisadora e professora da Universidade Federal do Amazonas, é fruto de sua pesquisa desenvolvida no seu mestrado na Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro.

O livro de Keith Valéria de Oliveira Barbosa, pesquisadora e professora da Universidade Federal do Amazonas, é fruto de sua pesquisa desenvolvida no seu mestrado na Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro.