Registros Imortais | E. E. Santos

É no contexto geral do contorno das aflições espirituais que a obra “Registros Imortais” sobrevém, pela Editora Vinha de Luz, em tiragem datada de 2013 e reeditada no ano de 2020, a partir da transcrição de psicofonias, entendidas pela Doutrina Espírita como falas de espíritos através de um medianeiro. As “Palavras Iniciais” do organizador, Eugênio Eustáquio dos Santos (1958), insurgem contando a história pregressa que teve como desfecho a publicação deste livro, posto que, rico material concernente ao Espiritismo, supostamente extraviado, fortuitamente se revelou, abrindo espaço para análise, compilação e publicação de mensagens memoráveis dos idos de 1956 a 1958 (p. 16). Leia Mais

Tacky’s revolt: the story of an Atlantic slave war | Vincent Brown

Na esteira de seus outros trabalhos sobre escravidão e diáspora africana Vicent Brown2, professor da Universidade de Harvard, publicou em janeiro de 2020, Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War para debater de uma maneira revisionista três revoltas de escravos da Jamaica, dando a elas, especialmente a segunda, liderada por Apongo (nome africano do escravo Wager), que estourou na freguesia de Westmoreland, localizada no ocidente da ilha, uma importância histórica bem mais definida e profunda. A “Rebelião de Tacky”, em St. Mary também na região leste e a “Marcha de Simon”, que se desenvolveu nas regiões centrais da colônia, completam os eventos analisados. Leia Mais

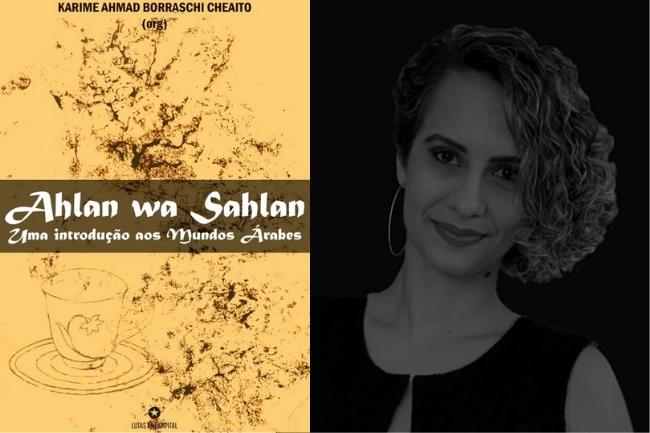

L’education physique de 1945 à nous jours: les étapes d’une démocratisation | Michaël Attali, Jean Saint-Martin

A obra em questão, publicada pelos professores Michaël Attali (Universidade de Rennes 2) e Jean Saint-Martin (Universidade de Strasbourg), foi primeiro publicada no ano de 2004, com reedições em 2009 e 2015. A edição ora analisada é de 2021, atualizada em relação às últimas alterações ocorridas no âmbito da escola francesa. O livro foi editado pela editora Armand Colin, como parte da coleção “Dynamique” organizada por Jean-Pierre Famose, André Rauch e Alfred Wahl. Leia Mais

Guia de visitação do Cemitério Israelita da Vila Mariana | R. Cytrynowicz

Do que se conhece das publicações existentes, o Guia de visitação do Cemitério Israelita da Vila Mariana é a primeira publicação no Brasil voltada a um cemitério judaico, que apresenta roteiros. A realização da obra tornou-se possível por meio do apoio da Secretaria de Cultura e Economia Criativa do Estado de São Paulo, por meio da aprovação em edital do Programa de Ação Cultural do ano de 2020. O livro é de autoria do historiador Roney Cytrynowicz, graduado em Economia, mestre e doutor em História Social pela Universidade de São Paulo, suas pesquisas tem como foco a história dos judeus no Brasil. Cytrynowicz (1990, 2000) é autor de obras sobre os judeus durante a 2ª Guerra Mundial e a barbárie do Holocausto. Também tem se dedicado à literatura infantil e a publicação em vários veículos de comunicação e científicos. Ainda, foi diretor do Arquivo Histórico Judaico Brasileiro, atual Centro de Memória do Museu Judaico de São Paulo, a principal instituição que preserva um grande acervo documental relativo à memória, à história e à cultura dos imigrantes judeus no país. Leia Mais

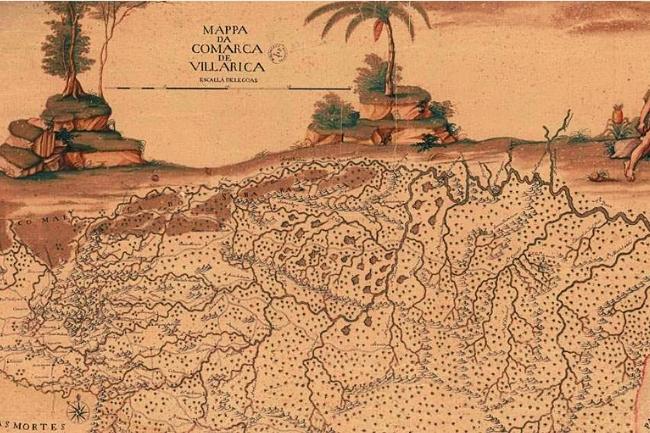

Exploration/religion and Empire in the sixteenthcentury Ibero-Atlantic world: a new perspective on the history of modern Science | Mauricio Nieto

La era de los descubrimientos supusieron una transformación social y cultural del continente europeo, relacionada con la aparición de nuevos actores y su geografía. América, y su relación con Europa, produjo cambios estructurales. Dentro de este proceso, el conocimiento producido en el siglo XVI por cosmógrafos, pilotos, cartógrafos y cronistas fue fundamental para consolidar del proyecto imperial español sobre el Nuevo Mundo. El desafío más grande de tal expansión imperial y religiosa fue el problema de “controlar a distancia”. Este, que es esencialmente un problema de comunicación, no se puede pensar desde la historia de la ciencia sin referirse a la relación entre religión, exploración e imperio. Mauricio Nieto (2022) nos relata el proceso de conquista y expansión española como una empresa enfocada en la identificación y el control de una ruta para realizar el cruce atlántico de manera segura y consistente durante el siglo XVI. Esta empresa necesitó la creación de complejas redes tecnológicas e instituciones dirigidas a solucionar tal desafío, y a sostener el imperio y sus relaciones en los territorios de ultramar, dominando el mar con sus barcos. Leia Mais

The religion of life: eugenics/race/and Catholicism in Chile | Sarah Walsh

Las trayectorias biográficas del ex dictador militar Augusto Pinochet y el ex presidente socialista Salvador Allende parecen tener puntos de encuentro. Ambos, nacidos en las primeras décadas del siglo XX, fueron testigos de una serie de cambios culturales, políticos y sociales en la historia contemporánea de Chile. Pinochet y Allende realizaron sus estudios secundarios en prestigiosos colegios en la ciudad de Valparaíso, y ambos compartieron valores sociales que emergieron como ejes claves del bienestar del país: la familia, los vínculos matrimoniales y el compromiso público por la nación. Leia Mais

Corpos inscritos: vacina e biopoder: Londres e Rio de Janeiro/ 1840-1904 | Myriam Bahia Lopes

O livro Corpos inscritos: vacina e biopoder: Londres e Rio de Janeiro, 1840-1904, da historiadora Myriam Bahia Lopes (2021), resulta de uma pesquisa pioneira sobre a vacinação antivariólica, esse “monumento da medicina científica”. Sua leitura é essencial para compreender as raízes históricas dos debates entre aqueles que são favoráveis e os que são contrários às vacinas. Mais do que isso: além de explicar posições científicas e ideológicas, recuperando a história das lutas em prol da vacinação, Myriam interroga com habilidade os interesses em jogo na construção de diversas experiências fundadoras da modernidade, tais como a formação da opinião pública, as tentativas de estabelecer um biopoder em meio às propostas de higienização e de saneamento urbanos, assim como o campo das disputas científicas fomentado pela imprensa dos dois últimos séculos. E ainda: o livro ensina o quanto as desconfianças em torno da vacinação possuem uma longa e movimentada história, tecida em meio à persistência de antigos receios diante da ameaça do contágio, mas também atravessada pela progressiva invenção de novas técnicas de imunização. Em vez de seguir uma suposta linearidade dos fatos, a autora apresenta um rico mosaico de narrativas médicas, políticas e jornalísticas, propondo hipóteses e questionamentos tão instigantes quanto essenciais para o entendimento da história do corpo e da vida urbana. Leia Mais

La ciudad latinoamericana: Una figura de la imaginación social del siglo XX | Adrián Gorelik

Publicado en 2022 por siglo veintiuno editores, ‘La ciudad latinoamericana. Una figura de la imaginación social del siglo xx’ de Adrián Gorelik propone un recorrido exhaustivo por muchas de las estaciones que ha atravesado aquella figura del pensamiento social y urbano que se sintetiza bajo el nombre de ‘ciudad latinoamericana’. Buenos Aires, Lima, Río de Janeiro, La Habana, Santiago de Chile, Bogotá, Caracas, Ciudad Guayana, Brasilia, México, Puerto Rico e incluso regiones y ciudades de Estados Unidos componen, se conectan y son atravesados en esta historia de la categoría ‘ciudad latinoamericana’ protagonizada y co-construida por y a través de redes, actores, instituciones y teorías móviles a la vez que localizadas.

Un lector incauto puede confundirse o llevarse una agria sorpresa frente al enfoque propuesto. En efecto, tal como se explicita rápidamente en el libro, no se trata del recorrido por la ciudad latinoamericana ‘realmente existente’, ya que esta – acotada, definida y en singular – no existe a los ojos de Gorelik. El foco, por el contrario, parte de entender la ciudad latinoamericana como una construcción cultural e intelectual cuyas formas, contornos y actores involucrados en su comprensión y producción varían a lo largo del tiempo. Leia Mais

Carnaval-ritual: Carlos Vergara e Cacique de Ramos | Maurício Barros de Castro

Com Carnaval-ritual: Carlos Vergara e Cacique de Ramos, Maurício Barros de Castro dá sequência à sua já extensa produção bibliográfica. Professor da Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro (Uerj), ele destaca-se por sua formação interdisciplinar: graduado em Comunicação Social, realizou mestrado em Memória Social na Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Unirio) e doutorado em História na Universidade de São Paulo (USP), tendo trajetória na pós-graduação vinculada a orientação de José Carlos Sebe Bom Meihy, um dos autores clássicos da História Oral no Brasil e de suas relações com a memória social.

Carnaval-ritual, em particular dialoga com vários livros escritos e organizados pelo autor na década de 2010, como Mestre João Grande: na roda do mundo1 , Estácio: vidas e obras2 , Zicartola: política e samba na casa de Cartola e Dona Zica3 , Relações raciais e políticas de patrimônio4, Gilberto Gil: Refavela5 e Arte e cultura: ensaios6, sem falar de sua participação no grupo responsável por Nos quintais do samba da Grande Madureira: memória, história e imagens de ontem e hoje.7 Em comum, esses trabalhos mapeiam as sociabilidades urbanas do Rio de Janeiro e do Brasil, os cruzamentos entre cultura popular e erudita, e as expressões artísticas, religiosas e musicais afro-brasileiras. A maior parte deles vincula-se, direta e indiretamente, ao projeto Museu Afro-digital8, que valoriza e divulga o patrimônio cultural da diáspora negra no Brasil e nas Américas. Leia Mais

Do U dy grudy ao Cantares: as vozes e os acordes da moderna canção popular piauiense | Hermano Carvalho Medeiros

A configuração do campo de estudos em torno da música popular vem se definindo, no âmbito da escrita da história do Brasil, como parte da virada historiográfica decorrente da ascensão de paradigmas teóricos e metodológicos vinculados à história social e à história cultural em universidades de diferentes regiões do país. Contemplando pesquisas que versam sobre temas diversos dentro desse universo, tais como a polifonia paulistana na década de 19301, o samba e suas conexões com o Estado Novo2, a Tropicália e suas controvérsias3, a chamada “música cafona”4, o rap5 e a música sertaneja6, tais produções permitiram que, para além do eixo Sul-Sudeste, ocorresse uma crescente regionalização do debate que põe sons e sentidos no foco de historiadores.

Investido desse manancial de referências, o historiador piauiense Hermano Carvalho Medeiros trilhou um percurso acadêmico cujos argumentos, de algum modo, buscavam estudar distintas modalidades de cultura, sobretudo no campo musical. Desde sua graduação, pautada na mitificação do poeta e letrista Torquato Neto em sua terra natal7, passando pelo seu mestrado, que objetivou compreender a denominada “polifonia musical” teresinense8, seus esforços como pesquisador concentram-se em inserir os circuitos sonoros daquele estado nordestino no concerto acadêmico nacional, possibilitando que ganhasse lugar na historiografia como temática autorizada pelos seus pares. Leia Mais

Mercados reproductivos: crisis/deseo y desigualdade | Sara Lafuente-Funes

A ampliação das bioeconomias 1 e dos processos de globalização tem reconfigurado os mercados reprodutivos. Esses processos têm se colocado como estratégias cada vez mais disseminadas de criação de novos modelos de negócios envolvendo a articulação da economia e a capitalização da vida em si, mercantilizando o vivo. Em muitas economias, os mercados assumem um lugar de destaque na área da saúde, sendo crescente a participação de empresas privadas em diferentes segmentos. Leia Mais

La Montaña del Quindío: Una frontera interior 1840-1880 | Alexander Betancourt e Sebastián Martínez

Durante el siglo XIX se configuró espacial y administrativamente la región que posteriormente fue conocida como el Gran Caldas, conformada por territorios que habían pertenecido a los Estados soberanos (durante la experiencia federalista) y a los departamentos del Cauca, Tolima y Antioquia (después de la constitución del 86). Como lo señalan Luis Javier Ortiz, Lina Marcela González y Óscar Almario García, tempranamente en el siglo XX surgieron interpretaciones del pasado de esta región donde el café y la «épica de la colonización antioqueña» ocuparon un papel preponderante en los análisis que pretendían estudiar las configuraciones económicas, sociales y políticas de un espacio que pertenecía a diferentes unidades administrativas1.

El libro reseñado trata sobre una parte significativa de este espacio, «la Montaña del Quindío», en un periodo donde el café aún no era el articulador de la región. El documento fue publicado recientemente por la Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira (utp). Los autores son Alexander Betancourt Mendieta, doctor en Estudios Latinoamericanos y profesor Investigador de la Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, y Sebastián Martínez Botero, doctor en Historia de América Latina y docente de la Escuela de Ciencias Sociales de la utp. Ambos autores se han interesado, desde hace varios años, por las representaciones, la frontera y la escritura del pasado del centro occidente colombiano en el siglo XIX y XX. Leia Mais

The Unsettled Plain: An Enviromental History of the Late Ottoman Frontier | Chris Gratien

«Çukurova è inesauribile»1: questa espressione dello scrittore Yaşar Kemal, riportata nei ringraziamenti da Chris Gratien è l’espressione più calzante per riassumere in una battuta l’ottimo saggio The Unsettled Plain. La frontiera del tardo periodo ottomano analizzata è la Cilicia: le sue pianure e i ritmi di vita dei suoi abitanti tracciano un percorso attraverso le diverse e convulse fasi finali dell’impero ottomano e degli albori della Repubblica di Turchia. L’autore analizza la regione della Cilicia nei suoi mutamenti da vilayet (provincia) ottomano dell’Ottocento a protettorato francese degli anni Venti del Novecento, alla sua trasformazione durante la Repubblica di Turchia. Leia Mais

L’era degli scarti | Marco Armiero

In un’intervista rilasciata per la rivista «Geography Notebooks» nel 2020, Marco Armiero ha definito l’ecologia politica come «quel campo di ricerca indisciplinato dove si guarda alle relazioni socioecologiche senza nascondere il potere e le diseguaglianze»1. Il libro L’era degli scarti. Cronache dal Wasteocene, la discarica globale, pubblicato per Einaudi nel 2021, si colloca precisamente lungo questa direttiva: proporre una narrazione politica capace di inquadrare la crisi socio-ecologica in atto a partire dal rapporto tra «scarti, diseguaglianze e il mondo che stiamo creando»2. Leia Mais

Oil Palm: A Global History | Jonathan E. Robins

The two main fields of reference of Jonathon Robins’ new book, Oil palm: a global history, are immediately revealed in its title: the history of commodities and global history. This work fits within the historiographical genre famously inaugurated by Sydney W. Mintz in 1985 1. It is not by chance that Robins, associate professor of History at the Michigan Technological University, investigated the history of another commodity, cotton (in the British Empire), before dealing with palm oil. Furthermore, the title indicates that the main character of the book is not the commodity itself but the tree producing it. In sum, it tells «the story of how humans used and lived with oil palms» 2. Surely this choice is also due to the fact that the oil palm tree, differently from the cotton plant for example, gives birth to more than one commodity: indeed, palm kernel oil played almost as fundamental a role in the globalization of palm products as the much more renowned palm oil (palm wine, on the other hand, never developed an appeal outside of African domestic markets). Leia Mais

Geel/la città dei matti. L’affidamento familiare dei malati mentali: sette secoli di storia | Renzo Villa

Durante l’acceso dibattito che si svolse, alla fine degli anni Sessanta dell’Ottocento, in seno al Consiglio provinciale di Cuneo per valutare la possibile realizzazione di un manicomio provinciale, si segnalò tra le altre una voce, quella del consigliere Michelini. Liberale e convinto sostenitore dell’idea di nazione, fattosi spesso notare per le chiare posizioni anticlericali1 e per la generosa partecipazione ai moti del 1821 2, il conte avanzò una critica radicale all’idea stessa del manicomio, in quanto luogo d’esclusione. La sua proposta, sviluppata «colla lettera diretta all’egregio dottore Parola»3, era insieme il frutto dell’esperienza di viaggiatore e di un orizzonte mentale aperto e riformista, tanto coraggioso quanto non in linea con le esigenze disciplinari dei tempi. Giovanni Battista Michelini, dopo aver visitato il villaggio belga di Geel, conobbe una modalità diversa di “curare” l’alienazione mentale e la propose alla Commissione Provinciale. Nel villaggio gli alienati soggiornavano presso le famiglie del contado «ove godono d’una libertà che non esclude le cure che esige il loro stato»4. Questa rivoluzione terapeutica aveva raggiunto una certa notorietà nel 1803, quando il prefetto del Dyle aveva deciso, dopo aver preso accordi con le autorità locali, di «trasportare a Geel i pazzi che si custodivano in Bruxelles»5. Esquirol, che visitò il villaggio nel 1821, sostenne che a Geel c’era una colonia di pazzi che si mandano da tutti gli angoli del Dipartimento e dei dipartimenti vicini. Questi infelici sono in pensione presso gli abitanti; passeggiano liberamente nelle contrade, mangiano coi loro ospiti e dormono in loro casa. Se si abbandonano a qualche eccesso, si mette loro dei ferri ai piedi, il che non li trattiene dall’uscire di casa. Questo strano traffico è da tempo immemorabile la sola risorsa degli abitanti di Gheel; non si è mai udito, che ne siano derivati degl’inconvenienti6. Leia Mais

Una guerra di nervi. Soldati e medici nel manicomio di Racconigi (1909-1919) | Fabio Milazzo

Il lavoro di Fabio Milazzo – docente e ricercatore per l’Istituto storico della Resistenza di Cuneo, oltre che collaboratore di diverse riviste storiche e autore di svariate pubblicazioni sul tema della devianza ma non solo1 –, si inserisce come un ulteriore e prezioso tassello nel mosaico delle storie che stanno emergendo dagli archivi degli ospedali psichiatrici, e che via via contribuiscono a illuminare di una luce sempre più vivida le diverse vicende della Grande guerra, un momento cruciale per la storia italiana, ma anche per quella, più specifica, della psichiatria. Leia Mais

Die Achse. Berlin-Rom-Tokio 1919-1946 | Daniel Hedinger

L’Asse Berlino-Roma-Tokyo – secondo la denominazione adottata, soprattutto nel mondo anglosassone, per definire l’insieme di accordi che unirono Italia, Germania e Giappone dal Patto anticomintern al Tripartito – appare ancora oggi uno dei costrutti politico-internazionali più controversi dell’età contemporanea. Onnipresente fino al termine della Seconda guerra mondiale tanto nella propaganda dei tre regimi quanto nelle rappresentazioni e nelle considerazioni strategiche dei loro avversari, nonché assunta come capo d’imputazione per “cospirazione contro la pace” nei processi di Norimberga e Tokyo, l’alleanza tripartita scomparve rapidamente dalla memoria pubblica del dopoguerra, oscurata da una percezione nazionale delle singole esperienze autoritarie e da una visione regionalizzata del conflitto mondiale, con la netta distinzione del teatro bellico europeo da quello asiatico-orientale e una gerarchia d’importanza che subordinava il secondo al primo. A partire dagli anni Cinquanta, la storiografia sul Tripartito si è concentrata prevalentemente sugli aspetti diplomatici e sui contatti bilaterali, ponendo al centro la Germania e i suoi rapporti con Italia e Giappone, mentre le relazioni italo-giapponesi erano liquidate come un prodotto secondario dell’avvicinamento italo-tedesco. In questa prospettiva l’Asse parve un’«alleanza senza alleati» 1, debole e «inefficace» 2 perché minata da insanabili contraddizioni interne – dipendessero queste dall’accesa rivalità ideologica tra Roma e Berlino oppure dall’innaturale collaborazione tra il razzismo nazista e un paese asiatico che aveva presentato una proposta di uguaglianza razziale alla Conferenza di pace di Parigi. Leia Mais

Clínica/laboratório e eugenia: uma história transnacional das relações Brasil-Alemanha | Pedro Muñoz

Pedro Muñoz is a young historian and psychologist who is influenced by the philosophy of Michel Foucault. Clínica, laboratório e eugenia: uma história transnacional das relações Brasil-Alemanha ( Clinic, laboratory and eugenics: a transnational history of Brazil-Germany relations ) is a partially modified version of his PhD dissertation, part of which he conducted at Freie Universität Berlin with a scholarship from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes) and Deutscher Akademischer Austauchdienst (Daad). His youth belies a classical approach to historiography. He is not a Rankean historian looking for absolute truths, but a creative researcher with a genuine appreciation for old and yellowed paper. For his dissertation and book, Muñoz visited 11 German archives and perused different issues of 23 journals. Leia Mais

Psiquiatria e política: o jaleco/a farda e o paletó de Antônio Carlos Pacheco e Silva | Gustavo Querodia Tarelow

Antonio Carlos Pacheco e Silva (1898-1998) nasceu no limiar do século, filho de abastada família paulista. Em seus textos memorialísticos, o renomado psiquiatra relatou o ambiente que o esperava quando veio ao mundo na capital de São Paulo: um lar “puro e coeso” ( Tarelow, 2020 , p.40). De certa forma, na obra Psiquiatria e política: o jaleco, a farda e o paletó de Antonio Carlos Pacheco e Silva, notamos que as noções atribuídas a esse lugar doméstico – “pureza” e “coesão” – serviram como coordenadas para suas atividades médicas e políticas ao longo da vida. Nelas se pautaram seu investimento em um ideal de povo brasileiro e suas contribuições como intelectual, principal tema que percorre a obra de Tarelow. Leia Mais

Tornar-se negro ou índio: a legalização das identidades no Nordeste brasileiro | Jan Hoffman French

O título é autoexplicativo: Tornar-se negro ou índio trata de processos identitários no último terço do século 20, experimentados por moradores das proximidades do Rio São Francisco, em territórios alagoano e sergipano. A pesquisa empreendida pela advogada Jan Hoffman French, que é também antropóloga, na Universidade de Richmon (EUA), foi desenvolvida nos anos 1990 e narra a transição identitária das populações Xocó e Mocambo: de trabalhadores rurais aparentados e próximos em território, a índios e quilombolas, respectivamente, que cultivaram interesses distintos nos anos 2000. Essa é a história substantiva da obra. Em termos metahistóricos, o livro trata do papel positivo do Estado e da globalização nesse processo de empoderamento (reconhecimento identitário e posse da terra) das populações subalternizadas. Mais importante, o livro informa sobre as implicações desta pesquisa para a produção de novo modelo teórico que aborda, conjuntamente, a emergência de identidades indígena e negra, em sociedades sustentadas por Estado democrático de direito: a criação do modelo de “legalização das identidades”. Trata-se de um conjunto de procedimentos e categorias que explicam o processo de construção de identidades no qual “a própria lei e suas interpretações” são modificadas “ao longo do tempo”, à medida em que “as pessoas por ela afetadas utilizam-na de diversas formas e, nesse processo, passam por uma transformação identitária” (p.34). Tais situações envolvem não apenas os agentes clássicos do Estado, mas também a Igreja Católica, ONGs, advogados, antropólogos e procuradores do Ministério Público (governamentalidade). Leia Mais

Em defesa de Constantino: o crepúsculo de um império e a aurora da cristandade | Peter Leithart

Nascido em 1959, Peter Leithart é bacharel em Inglês e História (1981) pelo Hillsdale College (Michigan, EUA), mestre em Artes e Religião (1986), mestre em Teologia (1987) pelo Westminster Theological Seminary (Philadelphia, EUA), e doutor em Teologia (1998) pela University of Cambridge (Inglaterra). Autor de diversos livros e artigos, é presidente do Theopolis Institute e atua como professor na Trinity Presbyberian Church (Birmingham).3 Leia Mais

Antipatriotas del agua. Conflictos y grupos de interés en el franquismo | Francesco D’Amaro

El libro a reseñar tiene como eje central las disputas sobre el agua en España durante el régimen de Franco. Sus principales fuentes proceden de los archivos de varias instituciones de regantes (Real Acequia del Júcar y Federación Nacional de Comunidades de Regantes). Además, se complementa con otras procedentes de la dictadura franquista, en especial las del Sindicalismo Vertical. A través de ellas, el autor disecciona los difíciles equilibrios entre el Estado dictatorial y los poderes tradicionales en el heterogéneo escenario del mundo rural.

La obra es el resultado de una tesis doctoral que ya había tenido notables anticipos en forma de artículos. Al tratarse de un autor que se ha movido entre dos historiografías, la italiana y la española, el ejercicio de historia comparada se realiza aquí con una acusada naturalidad, integrando los debates más interesantes en el texto. En general, son mejor conocidos los consorzi di bonifica, instituciones para el regadío implementadas en Italia antes de la II Guerra Mundial, que las entidades surgidas en torno al riego en España. Leia Mais

Los últimos años de la reforma agraria mexicana/ 1971-1991: una historia política desde el noroeste | Luis Aboites

Uno de los principales temas dentro de la historiografía agraria mexicana es el de la reforma agraria. Resultado del movimiento armado iniciado en 1910, esta reforma ha sido estudiada en miles de páginas en donde se destacan las políticas impulsadas por el Estado posrevolucionario, el número de hectáreas repartidas, los problemas que trajo su puesta en práctica y su culminación con la promulgación de la reforma al artículo 27 constitucional en el año de 1992, por solo mencionar algunos de los aspectos que se han abordado. Este último punto, el fin de la reforma agraria, es el objeto de estudio de la obra que aquí se reseña.

Los últimos años de la reforma agraria mexicana es un libro que nos presenta una historia política de los últimos 20 años del reparto agrario. Desde una perspectiva en donde se conecta lo regional con lo nacional, este trabajo busca rebasar la interpretación que sitúa como grandes protagonistas del fin de la reforma agraria a las políticas neoliberales impulsadas en México desde la década de los años ochenta y al autoritarismo del régimen de partido único, encabezado por el Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI). En contraposición con esta postura y como una de las principales contribuciones de esta investigación, el autor realiza una crítica puntual a la estatolatría de cierta historiografía que ha centrado su análisis en la figura presidencial, en las políticas estatales y en la historia de la reforma agraria dividida en sexenios, para poner mayor atención en los cambios demográficos y económicos, así como en el papel de los actores, específicamente “en los enemigos de la reforma agraria” (p. 20), por lo que, en última instancia, se trata principalmente de una historia política de los conflictos entre el antiagrarismo de los hacendados-empresarios expropiados y el Estado posrevolucionario, “en especial contra el presidencialismo y el Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI)” (p. 21), que culminó con el triunfo de los primeros. Leia Mais

Senderos de la historia. Miradas y actores en medio siglo de historia rural | Alba Díaz-Geada e Lourenzo Fernández Prieto

Esta obra supone una notable actualización y balance de la historiografía agraria española de las últimas décadas. Siguiendo la tradición establecida por el Seminario de Historia Agraria (SEHA), actualmente Sociedad de Estudios de Historia Agraria, propone un debate colectivo en torno a las modificaciones operadas en enfoques, métodos y sujetos que han sido abordados por la historia agraria en las épocas moderna y contemporánea. Así, supone un encuentro de diversas generaciones de historiadores que, desde la década de 1970, se han esforzado, desde publicaciones, seminarios y congresos, en mantener y extender una escuela historiográfica de gran calidad, modélica para otros campos de la historia contemporánea por su fomento de una interdisciplinariedad que, por definición, acoge en su seno la historia agraria por su porosidad y conexiones científicas con la historia política, económica, social o cultural.

Senderos de la historia viene por tanto a significar un nuevo impulso al seguir la estela de la gran renovación que implicó, veinte años antes, la publicación de El pozo de todos los males1. En este libro se superaron las tesis historiográficas más clásicas sobre el “atraso” de la agricultura española situando nuevas perspectivas en torno a variables analíticas como las características del cambio tecnológico, las relaciones económico-ambientales o la distribución de la renta y la riqueza. De este modo, concluyó que carecía de sentido caracterizar como “atrasada” la evolución de la agricultura y la economía españolas durante la fase expansiva capitalista culminada en la década de 1930, puesto que dicha evolución fue consecuencia de reglas sociales articuladas para impulsar el crecimiento en un contexto de gran desigualdad y en un contexto ambiental de posibilidades limitadas, creando un desarrollo social muy precario y con escasas capacidades de reproducción estable. Una década más tarde, la evolución de la historia agraria española conoció otro importante jalón con la publicación de Sombras del progreso2, donde se profundizó en estas tesis. Leia Mais

Fields of Revolution: Agrarian Reform and Rural State Formation in Bolivia/1935- 1964 | Carmen Soliz

The question of agrarian reform in Latin America has recently resurfaced as a topic of historical inquiry. In this context of renewed attention to the political nature of land reform, scholars have begun to ask: which land reform was the most radical? While the success of Mexico’s agrarian reform has been hotly contested for decades, gains from Guatemala’s reform were reversed after the 1954 coup, and Cuba’s 1959 land reform suddenly appears less radical when paired against the 1969 agrarian reform that cooperativized land in Peru. Bolivia’s 1953 land reform has seldom been interpreted as more transformational, far-reaching, or long-lasting than these or other Latin American examples. But Carmen Soliz’s methodically researched book, Fields of Revolution: Agrarian Reform and Rural State Formation in Bolivia, 1935-1964, seems to suggest just that.

Standard depictions of Bolivia’s 1952 revolution have regarded its agrarian reform law as either incomplete or a failure. Indeed, when Cuban revolutionaries embarked on their own project of agrarian reform in 1959, they looked to the Mexican and Bolivian cases for inspiration but concluded that neither had been successful enough to elicit emulation. The scholarship on Bolivia’s 1952 revolution, moreover, has continued to interpret Bolivia’s agrarian reform as limited, top-down, and applied in a clientelist manner. Soliz’s book overturns those conceptions and brings to light an entirely different reality, one forged in the highlands of rural Bolivia, where peasants expanded the limits of the agrarian reform law, won a new future for themselves, and changed the outlook of Bolivian politics. Leia Mais

Colonial cataclysms: climate/landscape/and memory in Mexico’s Little Ice Age | Bradley Skopyk

Difícilmente podríamos decir que el clima es una novedad para las ciencias históricas, en especial cuando los estudios abarcan el mundo agrario. En el caso de la literatura sobre el espacio que hoy conforma el territorio mexicano, desde fines del siglo pasado podemos encontrar historiadores y arqueólogos realizando análisis que involucran eventos de sequías, heladas, sedimentación e inundaciones. Aunque estos antecedentes no han desembocado en una historia del clima con la misma expresión que tienen otros tipos de abordajes y narrativas, lo cierto es que en los últimos años aquellos especialistas atentos a las variables y variabilidades climáticas han logrado identificar y/o replantear problemáticas que antes eran vistas desde un mareante antropocentrismo. Asimismo, sus estudios producen cada vez más metodologías nuevas para sacar e interpretar datos climáticos (proxy data) presentes en los archivos o producidos por otras ciencias. Es justo en este presente historiográfico, y en diálogo con él, que vino a luz el libro Colonial Cataclysms: climate, landscape, and memory in Mexico’s Little Ice Age, escrito por el historiador Bradley Skopyk.

Colonial Cataclysms es un estudio con la mirada puesta sobre México central durante el dominio ibérico y constituye una aportación mayúscula a la historia de la región analizada y un acercamiento novedoso a los procesos ocurridos en el marco de la Pequeña Era del Hielo (PEH en adelante). Con base en una serie de variaciones climáticas elaborada por el autor mediante la correlación entre las dinámicas del clima, los conocimientos morfodinámicos, estudios dendrocronológicos y el archivo, este trabajo se desarrolla a partir del argumento de que entre principios del siglo XVI y fines del siglo XVIII, México central vivió una etapa de flujo ambiental, social y político directamente vinculada a la existencia de dos cataclismos. Según el autor, estos cambios abruptos tuvieron orígenes diferentes y sus rasgos quedaron incrustados en el paisaje físico y documentado. Mientras el primero, de carácter más climático, se conformó a partir de una fase de la PEH que se prolongó hasta fines del siglo XVII y se caracterizó por picos de humedad y bajas temperaturas, el segundo tuvo una manifestación más geomórfica, distinguiéndose por una rápida transformación del campo, donde los paisajes palustres fueron sucedidos por otros de laderas áridas y valles sedimentados y disecados. Leia Mais

Conhecimento desde dentro: os afro-sul-americanos falam de seus povos e suas histórias | Sheila S. Walker

Sheila Walker, em um intenso movimento afrogênico, presenteia-nos com “Conhecimento desde dentro: Afro-Sul-Americanos falam de seus povos e suas histórias”. A obra foi lançada no I SEMILLAH – I Seminário Latino-Afro-Hispânico, nas dependências da Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ), Campus Nova Iguaçu, em 2018. Tanto a primeira publicação em espanhol (2010) quanto sua tradução (2018) são frutos de ações coletivas. Leia Mais

Comprender y juzgar. Hacer Justicia en las ciencias sociales | Patricia Funes

Los juicios por los crímenes cometidos durante la última dictadura conforman un elemento particular, dinámico y significativo en la historia política argentina contemporánea. Es comprensible que a partir de esa riqueza los juicios se hayan convertido en un objeto de interés para las ciencias sociales, despertando diversos interrogantes sobre la vida social que exceden ampliamente el lenguaje y los objetos del derecho. Inversamente, ha acontecido en los juicios contemporáneos, desde su reapertura a mediados de los dos mil, un fenómeno novedoso y particular: el conocimiento producido desde las ciencias sociales sobre aquel pasado abyecto ha despertado un creciente interés en las lógicas y praxis de los tribunales, recurriendo a las voces de los científicos sociales como herramientas de la acción judicial. Y en ese marco, como analizan Funes y Catoggio en su introducción al volumen aquí presentado, se han producido transformaciones en ambos campos, intersecciones y desencuentros, fruto de esa cooperación. Leia Mais

La Contraofensiva: el final de Montoneros | Hernán Confino

En la segunda mitad de 1979, el poeta y militante Juan Gelman escribió algunas de sus famosas Notas (Calella de la Costa/París/Roma), entre cuyos versos se encuentra el que da título a esta reseña. Pocos meses antes, junto a Rodolfo Galimberti y otros compañeros difundieron su alejamiento de Montoneros en el periódico francés Le Monde, cuestionando el rumbo emprendido por su Conducción. El trabajo de Hernán Confino, enfocado en la historia de la organización y de sus militantes entre la salida orgánica del país y la llamada Contraofensiva, me recordó a esa imagen de los pedacitos rotos que construyó la “Nota XII”. Por un lado, porque ese sueño revolucionario al que refería Gelman está presente en las páginas de La Contraofensiva: el final de Montoneros, junto a la historia de las decenas de compañeros caídos en el camino. Por otro, porque la investigación de Confino debió lidiar con la fragmentación de las memorias y la dispersión de documentos que un sueño como aquel dejó al romperse. Leia Mais

ESMA. Represión y poder en el centro clandestino de detención más emblemático de la última dictadura argentina | Marina Franco, Claudia Feld

ESMA. Represión y poder en el centro clandestino de detención más emblemático de la última dictadura argentina parte de un interrogante central: ¿por qué la ESMA? Por todas las preguntas abiertas más allá de, y gracias a, testimonios de sus sobrevivientes, procesos judiciales y numerosos trabajos previos sobre este centro clandestino que funcionó en la ciudad de Buenos Aires, durante toda la última dictadura argentina (1976-1983). Leia Mais

O legado de Marte. olhares múltiplos sobre a Guerra do Paraguai | Marcello José Gomes Loureiro

Marcello José Gomes Loureiro | Imagem: Mondes Americains

Guerras são episódios traumáticos que marcam de maneira indelével países e populações. Por tratar-se do último grande conflito bélico platino e por sua extensão, dramaticidade e sanguinolência, a Guerra do Paraguai marcou a história das Américas. Dela quase todas as quatro nações envolvidas saíram prejudicadas, sobretudo o Paraguai, todas passaram por mudanças, tanto nas relações entre si, quanto nas suas vidas políticas e institucionais internas, e suas populações tiveram as vidas alteradas.

O Brasil não estava preparado para uma guerra de tamanha envergadura como a campanha contra o Paraguai, e teve que mobilizar às pressas a população para constituir um exército, transformando civis em combatentes. Além disto, o governo imperial teve que enfrentar uma série de desafios, militares, diplomáticos e de política interna. Os seis anos do conflito desviaram a atenção do governo das reformas internas; levou a enormes gastos com a luta, gerando um déficit público que persistiu até 1889; explicitou as contradições de uma sociedade que tinha a escravidão como principal instituição; colocou à prova elementos definidores das relações sociais e da cidadania e transformou o exército em importante agente político. Além disto, os historiadores são praticamente unânimes em considerar que a guerra marcou o princípio de erosão do sistema monárquico. Leia Mais

Utopias latino-americanas: política, sociedade, cultura | Maria Ligia Coelho Prado

Maria Ligia Coelho Prado | Imagem: Revista Pesquisa

O livro Utopias latino-americanas: política, sociedade, cultura, publicado pela editora Contexto em 2021, constitui-se não apenas em uma valiosa contribuição aos estudos acadêmicos especializados, mas também em uma obra acessível a um público leitor mais amplo, interessado pela história da nossa região. É organizado pela historiadora Maria Ligia Coelho Prado, professora emérita da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da USP.2 Prado, que iniciou a docência em História da América em 1975, é também uma das responsáveis por estruturar a área no Brasil, por meio da orientação de gerações de historiadores – hoje professores em diferentes instituições pelo país – e de sua participação na fundação e organização da Associação Nacional de Pesquisadores e Professores de História das Américas (ANPHLAC), a qual presidiu entre 1998 e 2000.3 Foi coordenadora do Projeto Temático/Fapesp Cultura e Política nas Américas: Circulação de Ideias e Configuração de Identidades (séculos XIX e XX), cujas atividades se estenderam entre 2007 e 2011, e primeira coordenadora do Laboratório de Estudos de História das Américas (LEHA) do Departamento de História da USP, entre 2009 e 2012.4 É autora e coautora de diversos trabalhos, que se tornaram referência dentro da produção historiográfica brasileira acerca das Américas, aos quais se soma esta nova contribuição, idealizada para comemorar seu aniversário de 80 anos.

Percorrendo o sumário do livro, dois aspectos nos surpreendem. Em primeiro lugar, o grande número de pesquisadores que Maria Ligia Prado conseguiu reunir, espalhados por universidades brasileiras e estrangeiras. Em segundo lugar, a variedade de “utopias latino-americanas” contempladas na obra, distribuídas em cinco diferentes seções e em 22 capítulos, que fazem jus ao título escrito no plural. A preocupação com os projetos utópicos que tiveram lugar na América Latina articula os capítulos do livro, dando-lhe um fio condutor que percorre as suas páginas. As múltiplas utopias exploradas nas cinco seções colocam em cena numerosos personagens, conectando espaços e temporalidades, desde o século XIX até o nosso tempo presente. O Brasil aparece em diversos capítulos, seja em perspectiva comparada com outros países, seja dentro das reflexões a respeito dos projetos de integração da região. Leia Mais

Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching | Jarvis R. Givens

Jarvis R. Givens | Imagens: The Black Teacher Archive

Born in 1865 during the last years of the American Civil War, Carter H. Barnett was a teacher and the principal of Frederick Douglass School in Huntington, West Virginia, where he edited the West Virginia Spokesman and contributed to the state’s Black teacher association. Positioned on the edge of a tattered 1896 photograph, he stands to the right of fifty-some school children assembled in motley garb on the school steps, Garnett’s own studious dress and the hat held in his hand testament to his status as Principal of this six-room school.

In 1900 Garnett was fired after he alienated local white leaders by proposing a series of Black candidates for political office who were independent from the local Republican Party. His replacement, the beneficiary of the persistent vulnerability of Black educators and—likely unbeknownst to the white school board—his cousin, was Carter G. Woodson, now well-known and indeed lionized as the ‘Father of Black History Month.’ Barnett’s story is a particularly resonant instance of the many under-examined stories unearthed in Jarvis Givens’s Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching. Utilising Woodson as a centripetal focus, Givens unveils the full tapestry of Black education life, juxtaposing the fortunes and misfortunes of a realm “always in crisis; always teetering between strife and hope and prayer” (p. 22).

Givens, an assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, maps this liminal position by excavating a pedagogical heritage of ‘fugitivity’, following the insights of theorists including Édouard Glissant, Saidiya Hartman, and Nathaniel Mackey. Invoking Mackey’s conception of the “fugitive spirit” of Black social life more broadly (p. vii), Fugitive Pedagogy describes the everyday acts of subversion Black teachers employed to teach students about Black history and heritage amid “persistent discursive and physical assaults.” (p 34). As Givens takes pains to emphasise, these acts were not isolated episodes but instead “the occasion, the main event”, representing the visible aspects of an “overarching set of political commitments” that dated to the period of enslavement and continued to be anchored in celebrations of the folk heroism of the fugitive slave (p. 16). The fugitive slave’s example symbolised a space of existence outside of prescribed racial orders, where African Americans could collectively assert their capacity to be educated, rational, and human. In the words of Master Hugh from The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, a slave who knew how to write was “running away with himself” (p. 12).

A great strength of this analytic, as opposed to resistance or freedom, is to emphasise that Black educational efforts were always fated to struggle against centuries of legislation and beliefs that denied Black educability. Incorporating Achille Mbembe’s Critique of Black Reason, Givens suggests that this “chattel principle” that rendered African-descended peoples fungible property to be exchanged by slaveholders denied their potential rationality, catalysing subsequent antiliteracy laws (p. 10). Slaves were to have “only hands, not heads”, hence the declaration of legislation following 1739’s Stono Rebellion that “the having of slaves taught to write, or suffering them to be employed in writing, may be attended with great inconveniences” (p. 11). Locating Black educators in the ‘Afterlives of Slavery’, Givens thus suggests that to be Black and educated has always represented “an insistence on Black living, even amid the perpetual threat of Black social death” (p. 10).

Fugitivity also voices the affective and embodied natures of teaching, where classrooms underwent “aesthetic transformation… to defy the normative protocols of the American School” (p. 204). For Givens, education is corporeal, embodied, and freighted with emotional resonance, its putative impossibility under dominant racial scripts “etched into Black flesh” (p. 20). Conversely, miseducation and antiblack curricular violence are situated as symbiotic with physical violence, hence the frequent quotation of Woodson’s assertion “there would be no lynching if it did not start in the schoolroom.” (pp. 95-96). Thematically, Givens thus emphasises Black education as a learning experience, something recovered by trawling a “patchwork of sources” from a diverse archive to privilege the often understudied experiences of Black students themselves and uncovering that common contradiction between “what they said or wrote” (p. 20).

Givens’s “collage of fugitive pedagogy” (p. 24) is constellated around the “particular, emblematic narrative” (p. 4) of Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950), the author, historian, and founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). As opposed to echoing Jacqueline Goggin and Pero Galgo Dagbovie’s accomplished biographies of Woodson, Fugitive Pedagogy analyses Woodson in constant relation to the ASALH’s broader network of scholars to demonstrate how Woodson “inherited a tradition and then played a crucial role in expanding it” (p. 16). (1) By effectively dethroning Woodson, this networked approach paints a more expansive portrait than the patrilineal tendency to centre the individual achievements of this ‘father’ of Black Studies.

For example, Givens’s first chapter provides a fresh perspective on the already well-examined subject of Woodson’s life from 1875-1912 by emphasising his socialization into a vibrant pre-existing “black educational world” (p. 26). This deliberately privileges Woodson the teacher over Woodson the later scholar, highlighting how reading newspapers to the Civil War veterans he worked alongside in West Virginia’s coal mines and witnessing his teachers, frequently themselves formerly enslaved men, allowed Woodson to develop “a studied perspective on the distinct vocational demands of being a black teacher” (p. 26). Taking Woodson as emblematic of the first post-emancipation school generation thus stresses the continuities in Black education’s striving against a pre and post-emancipation antiblack social order, revealing how teaching the formerly enslaved consequently remained “an act of unmaking the terms of their relation to the word and world” (p. 35).

Chapter Two highlights how Woodson’s desire to denaturalize prevailing forms of scientific judgement found an “institutional embodiment” in the ASALH, one instance of Woodson’s wider designs to form a Black “counterpublic” (p. 71). Whilst this is also well-trodden ground, the fugitive pedagogy motif nonetheless helps to explain the Association’s shift from the interracial historical alliance conceptualized in 1915 to its more polemic form in the 1930s. This was, Givens argues, a direct response to the epistemological violence of racist films such as Birth of the Nation and the physical violence of contemporary race riots such as 1919’s ‘Red Summer.’ In a position of eternal vigilance, the Association was thus portrayed “standing like the watchman on the wall, ever mindful of what calamities we have suffered from misinterpretation in the past and looking out with a scrutinizing eye for everything indicative of a similar attack” (p. 62).

Chapter Three moves to embed Woodson in a distinct tradition of Black educational thought, a literature of educational criticism that sought to counter the disfiguring of Black knowledge within American public life. As opposed to emphasising the barriers preventing access into American schools and universities, Givens instead underscores the “epistemological underpinnings of education provided to those who made it past these barriers” (p. 97). Thus, Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro (1933) critiqued the “imitation resulting in the enslavement of his mind”, particularly from institutions like Harvard which rendered its students “blind to the Negro” and unable to “serve the race efficiently” (pp. 98-99). In the most theoretically expansive section of Fugitive Pedagogy, Givens articulates this Woodsonian critique of pedagogical ‘mimicry’ to the adjacent conceptions of several extra-American Black thinkers regarding the disfiguring of Black knowledge: Aimé Césaire’s ‘thingification’, Sylvia Wynter’s ‘narrative condemnation’, and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o’s ‘cultural bomb.’

Chapter Four too ballasts fugitive pedagogy in the remembrance of the Black fugitive as an “an archetype who symbolized Black people’s political relationship to the modern world and its technologies of schooling” (p. 128). This archetype indicates the wider use of Black historical achievements as models for present political action within textbooks that sought to vindicate Black intellectual and political life by recalling the full history of resistance within the Black diaspora. In this sense, Givens concludes, the Black textbook was “itself a literary genre inaugurated by runaway slaves” (p. 158). This tradition rendered curricular violence visible, distilling the possibility of resistance by evoking a Black aesthetic that situated subversion and defiance as long-standing threads of Black existence.

Chapter Five looks to connect Woodson to a cadre of Black schoolteachers. Adapting the term “abroad marriages”, originally applied to those enslaved who married those living on different plantations, Givens shows how Woodson the ‘abroad mentor’ utilised the Black press, the ASALH, and particularly Negro History Week to translate his ideas to school teachers, pausing along the way to examine the inequity in school provision and the restrictions on teaching they faced, particularly in the South. One notable example was the Negro Manual and Training High School in Muskogee, Oklahoma. In 1925 its Principal Thomas W. Grissom was forced to resign after officials found Woodson’s The Negro in Our History being taught, with the school board decreeing that nothing could be “instilled in the schools that is either klan or antiklan” (p. 168).

Finally, Chapter Six looks to centre students as “partners in [the] performance of fugitive pedagogy” by analysing biographical materials recounting the school days of prominent civil rights activists, politicians, and scholars including Angela Davis, John Lewis, and John Bracey (p. 199). Whilst subsequent activists are likely to be far from representative, Givens effectively emphasises the aesthetic ecology of the classroom and how the value systems undergirding school routines, rules, and projects including Negro History Week “inducted [students] as neophytes in a continuum of consciousness” (p. 222). This collection of visual narratives, Givens argues, formed an ‘oppositional gaze’, a disposition to question social technologies that perpetuated antiblack violence. The example of Congressman John Lewis is particularly resonant, as Givens shows Lewis prefiguring his later contribution to the sit-in movement by asking a public library in Troy, Alabama for library cards for him, his siblings, and his cousins despite their full awareness of the futility of this request.

If Fugitive Pedagogy has one weakness, it is the underplaying of intraracial differences inevitable within Givens’s artifice. Whilst Givens stresses that fugitivity is a variable practice, he asserts that “surely there are deviations, but they are not the concern here” (p. 16). Correspondingly, Fugitive Pedagogy makes no attempt to comprehensively trace variations in region, class, and gender. In a book of just over 300 pages, this is a pragmatic decision which avoids diluting the argumentative thrust. Yet consequential statements of intraracial equality are on occasion made rather too briefly. For example, Givens looks to identify the ASALH as “an intellectual project with Black Americans across age, class, and gender in mind,” defining his inclusion of gender here as a “careful assertion” (p. 84). Granted, Givens effectively illustrates that Black women consistently made up more than three-quarters of the profession and rose to prominent positions, with Mary McLeod Bethune becoming the ASALH’s President from 1936 to 1951. Yet this is not to say that Black women’s contributions were adequately recognised or recompensed, particularly given Patrice Morton’s suggestion that the ASALH failed to challenge many myths of Black womanhood prior to the late 20th century.(2)

Second, further research is needed to layer fugitive pedagogy into the full scope of Black institutional life, investigating how fugitive pedagogy translated to ancillary sites of education, including clubs, sporting societies, libraries, and churches. Givens consciously distances his argument from quantitative assessments of the inequality of educational provision yet this risks obscuring regional variations in resources and the vital ties between low wages, economic precarity, and professional vulnerability. Fugitive Pedagogy largely develops ‘upwards’ from individual acts of fugitivity, occasionally de-emphasising the institutional context. This means that readers hear little about mundane but vital factors including roofs, heating, lighting, desks, school grounds, teacher-pupil ratios, or the disproportionate private ownership of Black schools. With the firings of both Grissom and Barnett, Givens correspondingly emphasises the outcome rather than the process, occluding the logics and justifications of school boards and the pressures placed upon them by local (white) communities. Should an adequate archive exist, an ecological study focused on fugitive pedagogy within a single school would particularly flesh out Givens’s framework.

Third, given the roots of fugitive pedagogy in the discrete experience and memories of slavery, could other insurgent pedagogies employ fugitive practices? If not, there is a risk that the fugitive model shifts a further emotive and educative burden to Black teachers, compounding the long-standing tendency already recognised by Givens for Black teachers to double tax themselves to achieve liberatory ends. Givens suggests so, situating Black fugitive pedagogy as one discrete tradition within a broader genre of educational criticism that critiqued orthodox models of schooling, a purposive attempt to “leave room to consider… bodies of educational criticism by Native American educators and thinkers, Marxist educators, and feminist teachers and thinkers, among others who understand their political motivations for teaching to be in direct tension with the protocols and dominant ideology of the American school” (p. 251, cf.76). Further, recounting recorded acts of fugitivity necessarily underplays the longer slog of merely existing and making a living within white institutions, with all the undoubtedly uneasy cross-racial cooperation and interest convergence this entailed. When reckoning with this subject matter, any historian is condemned to see only the tip of the iceberg, only those acts visible in the archive through exorbitant chance and, more than often than not, only when refracted through the institutional memory of surveillance institutions. Whilst Givens has collected a vast archive of Black voices, there remains the risk of privileging more palpable disobedience over the dissemblances and circumlocutions which could allow Black teachers “wearing the mask” to articulate an activist ethos within the confines of objectivity.

These three areas for further investigation notwithstanding, Fugitive Pedagogy ultimately offers an engrossing reminder of the importance of collective education that is particularly resonant in the world of individualised algorithmic learning that followed the COVID-19 pandemic. Ambitious and theoretically virtuosic in exposition, magnetic and energizing in execution, the clarity of its theoretical interventions suggests that its broad brushstrokes will be imminently nuanced by other scholars empowered by the fugitive framework and its relevance to current pedagogical debates.

As the February 2022 victory of a diverse coalition against Indiana’s House Bill 1134 signals a growing resistance to anti-CRT legislation, Givens is particularly commendable for his insistence on Black education’s prescriptive moral force. A more diluted ‘anti-racist’ pedagogy within contemporary education that often tends towards the personal and psychological, towards diversity and inclusion, is cut short shrift compared to a progressive pedagogy that acknowledges the structural determinants of white supremacy. For Givens, education provides an alternative prospectus for living. If this may appear somewhat utopian, Fugitive Pedagogy at least provides a powerful argument for cross-professional solidarity between academia and schoolteachers. This will undoubtedly be furthered by Givens’s creation (alongside Princeton’s Imani Perry) of the Black Teacher Archives. As Givens notes, this disposition represents “an international refusal of contemporary trends where teachers are deprofessionalized in general and where black teachers in particular have been systemically alienated, often being positioned as unintellectual and nonpedagogical knowers” (p. 239).

Excavating Black education’s persistent fugitive ethos also emphasises that the ‘political’ education challenged by recent anti-CRT laws has only been rendered visible and legislatively-eradicable in proportion to white discomfort. Historicizing this ethos thus provides a warning against retreating to political ‘neutrality’ as such an option has never existed. Ultimately, Fugitive Pedagogy suggests that any pedagogy seeking to advance Black achievement is necessarily ‘political’, if only because the mere social fact of Black literacy confounds the founding principles of the American Republic.

To be sure, teachers in the present United States face their own dilemmas. Contemporary educators face not only an onslaught of anti-CRT legislation but also the dilemmas of retaining any activist impulse behind Black education within a racial liberalism that stresses the integration of Black history into multi-racial educational programmes disarticulated from the Black counterpublic sphere. As Givens recently recognised in The Los Angeles Review of Books: “We must also recognize… that [the] siloed inclusion of Black knowledge into mainstream institutions- often in defanged fashion- can only do so much to disrupt the self-corrective nature of said systems.” (3)

Jarvis Givens’s Fugitive Pedagogy places educational strivings at the heart of the Black freedom struggle, providing historians of the United States a digestible testament to the methodological interventions and activist orientations of recent historians of Black education. Suitable for both advanced undergraduates and the public, Givens’s work deserves a central role in syllabuses on the Black freedom struggle, the sociology of knowledge, and broader histories of resistance to educational domination. As the global education sector rebuilds following COVID-19, Fugitive Pedagogy cogently conveys this literature’s overwhelming emphasis on the virtues of disciplinary self-introspection and recovering shared professional heritages. If much of the fugitive tradition with its attendant varieties remains to be fully pieced out, Givens nonetheless articulates a grammar for struggle that can provide refortification to our own generation’s embattled teachers who choose to think otherwise. Teetering once more between “strife and hope and prayer”, Fugitive Pedagogy articulates a language that provides historical ballast for the present and argumentative weapons for the future.

Thomas Cryer (he/him) is a first-year AHRC-funded PhD student at University College London’s Institute of the Americas, where he studies memory, race, and, nationhood in the late-20th-century United States through the lens of the life, scholarship, and activism of the historian John Hope Franklin. [Twitter: @ThomasOCryer]

Notes

1 Pero Gaglo Dagbovie, The Early Black History Movement, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007) & Jacqueline Anne Goggin, Carter G. Woodson: A Life in Black History, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993).Back to (1)

2 Patricia Morton, Disfigured Images: The Historical Assault on Afro-American Women, (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991).Back to (2)

3 Jarvis Givens, ‘Fugitive Pedagogy: The Longer Roots of Antiracist Teaching,’ The LA Review of Books, August 18th, 2021.Back to (3)

Resenhista

Thomas Cryer - University College London.

Referências desta Resenha

GIVENS, Jarvis R. Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021. Resenha de: CRYER, Thomas. Reviews in History. Londres, n. 2465, sep. 2022. Acessar publicação original [DR]

Givens, an assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, maps this liminal position by excavating a pedagogical heritage of ‘fugitivity’, following the insights of theorists including Édouard Glissant, Saidiya Hartman, and Nathaniel Mackey. Invoking Mackey’s conception of the “fugitive spirit” of Black social life more broadly (p. vii), Fugitive Pedagogy describes the everyday acts of subversion Black teachers employed to teach students about Black history and heritage amid “persistent discursive and physical assaults.” (p 34). As Givens takes pains to emphasise, these acts were not isolated episodes but instead “the occasion, the main event”, representing the visible aspects of an “overarching set of political commitments” that dated to the period of enslavement and continued to be anchored in celebrations of the folk heroism of the fugitive slave (p. 16). The fugitive slave’s example symbolised a space of existence outside of prescribed racial orders, where African Americans could collectively assert their capacity to be educated, rational, and human. In the words of Master Hugh from The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, a slave who knew how to write was “running away with himself” (p. 12).

A great strength of this analytic, as opposed to resistance or freedom, is to emphasise that Black educational efforts were always fated to struggle against centuries of legislation and beliefs that denied Black educability. Incorporating Achille Mbembe’s Critique of Black Reason, Givens suggests that this “chattel principle” that rendered African-descended peoples fungible property to be exchanged by slaveholders denied their potential rationality, catalysing subsequent antiliteracy laws (p. 10). Slaves were to have “only hands, not heads”, hence the declaration of legislation following 1739’s Stono Rebellion that “the having of slaves taught to write, or suffering them to be employed in writing, may be attended with great inconveniences” (p. 11). Locating Black educators in the ‘Afterlives of Slavery’, Givens thus suggests that to be Black and educated has always represented “an insistence on Black living, even amid the perpetual threat of Black social death” (p. 10).

Fugitivity also voices the affective and embodied natures of teaching, where classrooms underwent “aesthetic transformation… to defy the normative protocols of the American School” (p. 204). For Givens, education is corporeal, embodied, and freighted with emotional resonance, its putative impossibility under dominant racial scripts “etched into Black flesh” (p. 20). Conversely, miseducation and antiblack curricular violence are situated as symbiotic with physical violence, hence the frequent quotation of Woodson’s assertion “there would be no lynching if it did not start in the schoolroom.” (pp. 95-96). Thematically, Givens thus emphasises Black education as a learning experience, something recovered by trawling a “patchwork of sources” from a diverse archive to privilege the often understudied experiences of Black students themselves and uncovering that common contradiction between “what they said or wrote” (p. 20).

Givens’s “collage of fugitive pedagogy” (p. 24) is constellated around the “particular, emblematic narrative” (p. 4) of Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950), the author, historian, and founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). As opposed to echoing Jacqueline Goggin and Pero Galgo Dagbovie’s accomplished biographies of Woodson, Fugitive Pedagogy analyses Woodson in constant relation to the ASALH’s broader network of scholars to demonstrate how Woodson “inherited a tradition and then played a crucial role in expanding it” (p. 16). (1) By effectively dethroning Woodson, this networked approach paints a more expansive portrait than the patrilineal tendency to centre the individual achievements of this ‘father’ of Black Studies.

For example, Givens’s first chapter provides a fresh perspective on the already well-examined subject of Woodson’s life from 1875-1912 by emphasising his socialization into a vibrant pre-existing “black educational world” (p. 26). This deliberately privileges Woodson the teacher over Woodson the later scholar, highlighting how reading newspapers to the Civil War veterans he worked alongside in West Virginia’s coal mines and witnessing his teachers, frequently themselves formerly enslaved men, allowed Woodson to develop “a studied perspective on the distinct vocational demands of being a black teacher” (p. 26). Taking Woodson as emblematic of the first post-emancipation school generation thus stresses the continuities in Black education’s striving against a pre and post-emancipation antiblack social order, revealing how teaching the formerly enslaved consequently remained “an act of unmaking the terms of their relation to the word and world” (p. 35).

Chapter Two highlights how Woodson’s desire to denaturalize prevailing forms of scientific judgement found an “institutional embodiment” in the ASALH, one instance of Woodson’s wider designs to form a Black “counterpublic” (p. 71). Whilst this is also well-trodden ground, the fugitive pedagogy motif nonetheless helps to explain the Association’s shift from the interracial historical alliance conceptualized in 1915 to its more polemic form in the 1930s. This was, Givens argues, a direct response to the epistemological violence of racist films such as Birth of the Nation and the physical violence of contemporary race riots such as 1919’s ‘Red Summer.’ In a position of eternal vigilance, the Association was thus portrayed “standing like the watchman on the wall, ever mindful of what calamities we have suffered from misinterpretation in the past and looking out with a scrutinizing eye for everything indicative of a similar attack” (p. 62).

Chapter Three moves to embed Woodson in a distinct tradition of Black educational thought, a literature of educational criticism that sought to counter the disfiguring of Black knowledge within American public life. As opposed to emphasising the barriers preventing access into American schools and universities, Givens instead underscores the “epistemological underpinnings of education provided to those who made it past these barriers” (p. 97). Thus, Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro (1933) critiqued the “imitation resulting in the enslavement of his mind”, particularly from institutions like Harvard which rendered its students “blind to the Negro” and unable to “serve the race efficiently” (pp. 98-99). In the most theoretically expansive section of Fugitive Pedagogy, Givens articulates this Woodsonian critique of pedagogical ‘mimicry’ to the adjacent conceptions of several extra-American Black thinkers regarding the disfiguring of Black knowledge: Aimé Césaire’s ‘thingification’, Sylvia Wynter’s ‘narrative condemnation’, and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o’s ‘cultural bomb.’

Chapter Four too ballasts fugitive pedagogy in the remembrance of the Black fugitive as an “an archetype who symbolized Black people’s political relationship to the modern world and its technologies of schooling” (p. 128). This archetype indicates the wider use of Black historical achievements as models for present political action within textbooks that sought to vindicate Black intellectual and political life by recalling the full history of resistance within the Black diaspora. In this sense, Givens concludes, the Black textbook was “itself a literary genre inaugurated by runaway slaves” (p. 158). This tradition rendered curricular violence visible, distilling the possibility of resistance by evoking a Black aesthetic that situated subversion and defiance as long-standing threads of Black existence.

Chapter Five looks to connect Woodson to a cadre of Black schoolteachers. Adapting the term “abroad marriages”, originally applied to those enslaved who married those living on different plantations, Givens shows how Woodson the ‘abroad mentor’ utilised the Black press, the ASALH, and particularly Negro History Week to translate his ideas to school teachers, pausing along the way to examine the inequity in school provision and the restrictions on teaching they faced, particularly in the South. One notable example was the Negro Manual and Training High School in Muskogee, Oklahoma. In 1925 its Principal Thomas W. Grissom was forced to resign after officials found Woodson’s The Negro in Our History being taught, with the school board decreeing that nothing could be “instilled in the schools that is either klan or antiklan” (p. 168).

Finally, Chapter Six looks to centre students as “partners in [the] performance of fugitive pedagogy” by analysing biographical materials recounting the school days of prominent civil rights activists, politicians, and scholars including Angela Davis, John Lewis, and John Bracey (p. 199). Whilst subsequent activists are likely to be far from representative, Givens effectively emphasises the aesthetic ecology of the classroom and how the value systems undergirding school routines, rules, and projects including Negro History Week “inducted [students] as neophytes in a continuum of consciousness” (p. 222). This collection of visual narratives, Givens argues, formed an ‘oppositional gaze’, a disposition to question social technologies that perpetuated antiblack violence. The example of Congressman John Lewis is particularly resonant, as Givens shows Lewis prefiguring his later contribution to the sit-in movement by asking a public library in Troy, Alabama for library cards for him, his siblings, and his cousins despite their full awareness of the futility of this request.

If Fugitive Pedagogy has one weakness, it is the underplaying of intraracial differences inevitable within Givens’s artifice. Whilst Givens stresses that fugitivity is a variable practice, he asserts that “surely there are deviations, but they are not the concern here” (p. 16). Correspondingly, Fugitive Pedagogy makes no attempt to comprehensively trace variations in region, class, and gender. In a book of just over 300 pages, this is a pragmatic decision which avoids diluting the argumentative thrust. Yet consequential statements of intraracial equality are on occasion made rather too briefly. For example, Givens looks to identify the ASALH as “an intellectual project with Black Americans across age, class, and gender in mind,” defining his inclusion of gender here as a “careful assertion” (p. 84). Granted, Givens effectively illustrates that Black women consistently made up more than three-quarters of the profession and rose to prominent positions, with Mary McLeod Bethune becoming the ASALH’s President from 1936 to 1951. Yet this is not to say that Black women’s contributions were adequately recognised or recompensed, particularly given Patrice Morton’s suggestion that the ASALH failed to challenge many myths of Black womanhood prior to the late 20th century.(2)

Second, further research is needed to layer fugitive pedagogy into the full scope of Black institutional life, investigating how fugitive pedagogy translated to ancillary sites of education, including clubs, sporting societies, libraries, and churches. Givens consciously distances his argument from quantitative assessments of the inequality of educational provision yet this risks obscuring regional variations in resources and the vital ties between low wages, economic precarity, and professional vulnerability. Fugitive Pedagogy largely develops ‘upwards’ from individual acts of fugitivity, occasionally de-emphasising the institutional context. This means that readers hear little about mundane but vital factors including roofs, heating, lighting, desks, school grounds, teacher-pupil ratios, or the disproportionate private ownership of Black schools. With the firings of both Grissom and Barnett, Givens correspondingly emphasises the outcome rather than the process, occluding the logics and justifications of school boards and the pressures placed upon them by local (white) communities. Should an adequate archive exist, an ecological study focused on fugitive pedagogy within a single school would particularly flesh out Givens’s framework.

Third, given the roots of fugitive pedagogy in the discrete experience and memories of slavery, could other insurgent pedagogies employ fugitive practices? If not, there is a risk that the fugitive model shifts a further emotive and educative burden to Black teachers, compounding the long-standing tendency already recognised by Givens for Black teachers to double tax themselves to achieve liberatory ends. Givens suggests so, situating Black fugitive pedagogy as one discrete tradition within a broader genre of educational criticism that critiqued orthodox models of schooling, a purposive attempt to “leave room to consider… bodies of educational criticism by Native American educators and thinkers, Marxist educators, and feminist teachers and thinkers, among others who understand their political motivations for teaching to be in direct tension with the protocols and dominant ideology of the American school” (p. 251, cf.76). Further, recounting recorded acts of fugitivity necessarily underplays the longer slog of merely existing and making a living within white institutions, with all the undoubtedly uneasy cross-racial cooperation and interest convergence this entailed. When reckoning with this subject matter, any historian is condemned to see only the tip of the iceberg, only those acts visible in the archive through exorbitant chance and, more than often than not, only when refracted through the institutional memory of surveillance institutions. Whilst Givens has collected a vast archive of Black voices, there remains the risk of privileging more palpable disobedience over the dissemblances and circumlocutions which could allow Black teachers “wearing the mask” to articulate an activist ethos within the confines of objectivity.

These three areas for further investigation notwithstanding, Fugitive Pedagogy ultimately offers an engrossing reminder of the importance of collective education that is particularly resonant in the world of individualised algorithmic learning that followed the COVID-19 pandemic. Ambitious and theoretically virtuosic in exposition, magnetic and energizing in execution, the clarity of its theoretical interventions suggests that its broad brushstrokes will be imminently nuanced by other scholars empowered by the fugitive framework and its relevance to current pedagogical debates.

As the February 2022 victory of a diverse coalition against Indiana’s House Bill 1134 signals a growing resistance to anti-CRT legislation, Givens is particularly commendable for his insistence on Black education’s prescriptive moral force. A more diluted ‘anti-racist’ pedagogy within contemporary education that often tends towards the personal and psychological, towards diversity and inclusion, is cut short shrift compared to a progressive pedagogy that acknowledges the structural determinants of white supremacy. For Givens, education provides an alternative prospectus for living. If this may appear somewhat utopian, Fugitive Pedagogy at least provides a powerful argument for cross-professional solidarity between academia and schoolteachers. This will undoubtedly be furthered by Givens’s creation (alongside Princeton’s Imani Perry) of the Black Teacher Archives. As Givens notes, this disposition represents “an international refusal of contemporary trends where teachers are deprofessionalized in general and where black teachers in particular have been systemically alienated, often being positioned as unintellectual and nonpedagogical knowers” (p. 239).

Excavating Black education’s persistent fugitive ethos also emphasises that the ‘political’ education challenged by recent anti-CRT laws has only been rendered visible and legislatively-eradicable in proportion to white discomfort. Historicizing this ethos thus provides a warning against retreating to political ‘neutrality’ as such an option has never existed. Ultimately, Fugitive Pedagogy suggests that any pedagogy seeking to advance Black achievement is necessarily ‘political’, if only because the mere social fact of Black literacy confounds the founding principles of the American Republic.